Diseases & Conditions

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a condition that develops in joints in children and adolescents. It occurs when a small segment of bone begins to separate from its surrounding region due to a lack of blood supply. As a result, the small piece of bone and the cartilage covering it begin to crack and loosen.

The most common joints affected by osteochondritis dissecans are the knee, ankle and elbow, although it can also occur in other joints. The condition typically affects just one joint; however, some children can develop OCD in several joints.

- In many cases of OCD in children, the affected bone and cartilage heal on their own, especially if a child is still growing.

- In grown children and young adults, OCD can have more severe effects. The OCD lesions have a greater chance of separating from the surrounding bone and cartilage and can even detach and float around inside the joint. In these cases, surgery may be necessary.

Anatomy

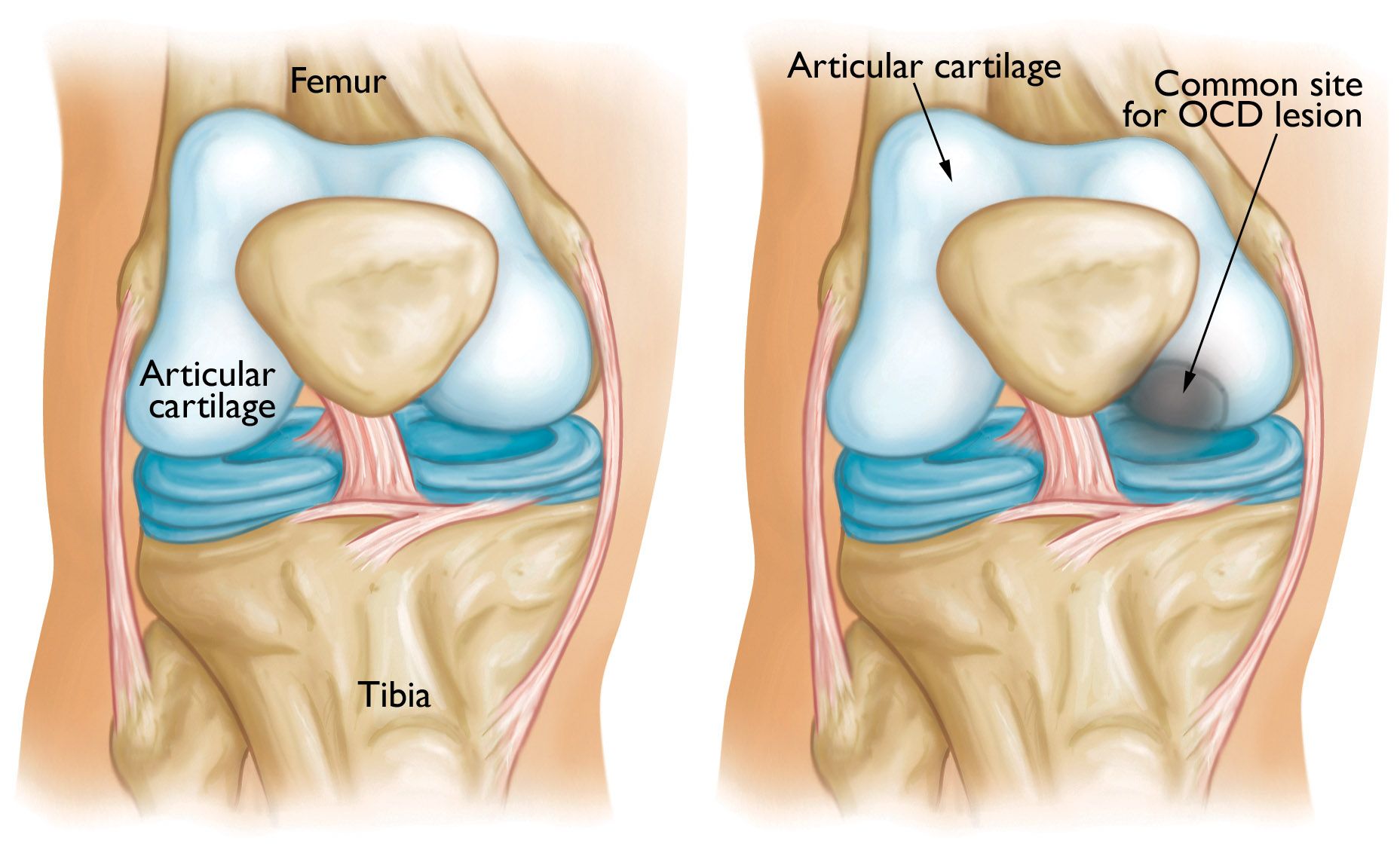

A joint is where the ends of bones meet, such as the knee, ankle, or shoulder joint. Healthy joints move easily because of a smooth, slippery tissue called articular cartilage. Cartilage covers and protects the ends of the bones where they meet to form a joint.

The most common location of OCD is in the knee at the end of the femur (thighbone).

Cause

It is not known exactly what causes the disruption to the blood supply and the resulting OCD. Doctors think it probably involves repetitive trauma or stresses to the bone over time.

Symptoms

- Pain and swelling of a joint — often brought on by sports or physical activity — are the most common initial symptoms of OCD.

- Advanced cases of OCD may cause joint catching or locking.

Doctor Examination

After discussing your child's symptoms and medical history, the doctor will perform a physical examination of the affected joint.

Other tests which may help the doctor confirm a diagnosis include:

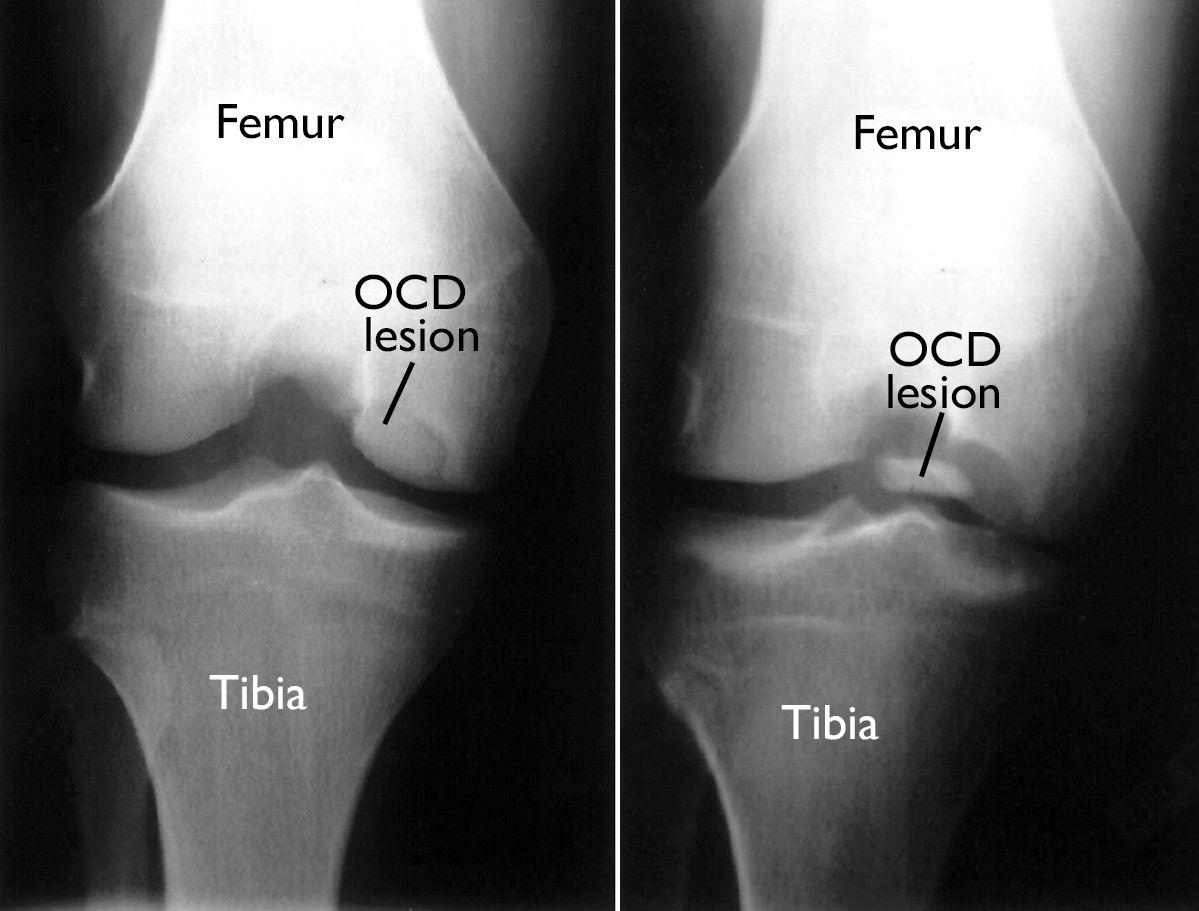

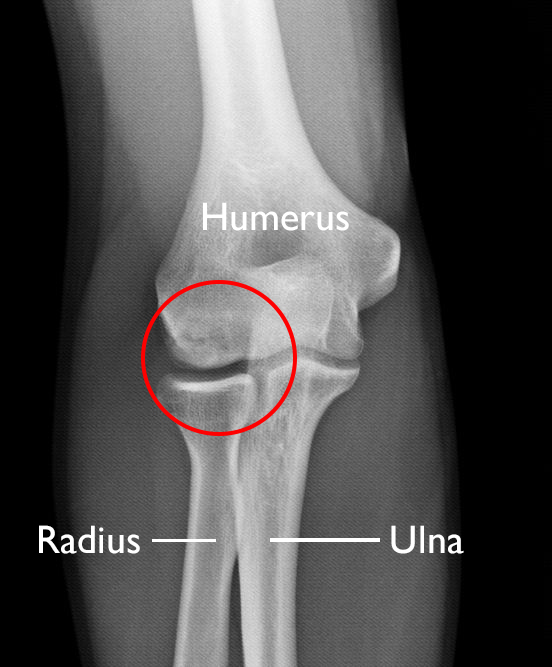

X-rays. X-rays provide detailed pictures of dense structures, like bone. An X-ray of the affected joint is essential for an initial OCD diagnosis, and to evaluate the size and location of the OCD lesion.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound. MRI and ultrasound can create better images of soft tissues, like cartilage. An MRI can help the doctor evaluate how much the cartilage around the bone is affected.

Treatment

Observation and Activity Changes

In many cases, OCD lesions in children and young teens will heal on their own, especially when the body still has a great deal of growing to do. Resting and avoiding vigorous sports until symptoms go away will often relieve pain and swelling.

Nonsurgical Treatment

If symptoms do not ease after a reasonable amount of time, the doctor may recommend:

- The use of crutches, or

- Immobilizing (splinting or casting) the affected arm, leg, or other joint for a short period of time

In general, most children start to feel better over a 2- to 4-month course of rest and nonsurgical treatment. They usually return to all activities as symptoms improve.

Your child's doctor may still follow the OCD lesion with X-rays at certain time points to check for healing.

Surgical Treatment

Your child's doctor may recommend surgery if:

- Nonsurgical treatment fails to relieve pain and swelling

- The lesion is showing signs of being wobbly or detached from the surrounding bone and cartilage

- The lesion is very large (greater than 1 centimeter in diameter)

- The lesion is in a teen who is nearing the end of growth and has a lower chance of healing with nonsurgical treatment

There are different surgical techniques for treating OCD, depending on the individual case:

- Drilling into the lesion to create pathways for new blood vessels to nourish the affected area. This will encourage healing of the surrounding bone.

- Holding the lesion in place with internal fixation (such as pins and screws).

- Replacing the damaged area with a new piece of bone and cartilage (called a graft). This can help regenerate (restore) healthy bone and cartilage in the area damaged by OCD.

Some of these techniques may be done arthroscopically. With arthroscopic surgery, the surgeon inserts a small camera and special instruments into the joint through small incisions. Other techniques may need to be done through a larger incision.

In general, crutches are required for about 6 weeks after surgical treatment, followed by a 2- to 4-month course of physical therapy to regain strength and motion in the affected joint.

A gradual return to sports may be possible after about 4 to 5 months, though this depends on which procedure was performed and the healing time.

To assist doctors in the management of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has conducted research to provide some useful guidelines. These are recommendations only and may not apply to every case. For more information: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee - Plain Language Summary - AAOS

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.