Diseases & Conditions

Muscular Dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of rare diseases that causes muscles to weaken and deteriorate. MD affects the voluntary muscles that control movement in the arms, legs, and trunk. It can also affect involuntary muscles, such as the heart muscles and respiratory muscles (the muscles that help you breathe in and out).

MD is a progressive disease, meaning that it worsens over time. Depending on the form of MD, children and adults may gradually lose the ability to walk and do other everyday activities. In the later stages of some forms of the disease, heart and breathing problems may develop, which can reduce the person's life expectancy significantly.

Although there is currently no cure for MD, there are medications that may slow the rate of muscle degeneration (weakening), as well as other treatment options to improve function and assist in activities of daily living.

Cause

Muscular dystrophy is a genetic disorder. It is caused by defects in the genes that produce proteins necessary for healthy muscle development and function.

In most cases, MD is inherited — it passes from parent to child. A few incidences of MD, however, may occur due to a new genetic abnormality. This is called spontaneous mutation.

Description

There are nine major types of MD affecting people of all ages, from infancy to middle age or later. Each form of MD differs in terms of the age of onset (when the signs and symptoms first appear) and which muscles are affected. How severe the symptoms are and how quickly the disease progresses also varies.

The two most common types of MD that affect children are:

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD)

- Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD)

Both DMD and BMD affect boys almost exclusively. They are sex-linked (X-linked) disorders that typically pass from a mother (who has no symptoms and is carrier for the mutated gene) to her son. Girls are rarely affected.

Both Duchenne MD and Becker MD cause:

- Weak muscles

- Lack of coordination

- Progressive disability (grows worse over time)

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

Duchenne MD begins with muscle loss in the pelvis, upper arms, and legs. The first signs and symptoms of DMD develop between the ages of 2 to 5 years. Symptoms include:

- Trouble walking, such as lateness in learning how to walk (older than 18 months), having a waddling gait, or walking on the toes or balls of the feet

- Trouble running or jumping because of weakness in leg muscles

- Frequent falls, stumbling, and trouble climbing stairs

- Trouble standing from a lying down or sitting position

- Reduced endurance

- Enlarged calf muscles

- Mild mental developmental delay (in some patients)

Many children with DMD lose their ability to walk by late childhood and require wheelchairs. As muscles continue to weaken in the back and chest, children develop curvature of the spine (scoliosis). By adolescence, DMD usually progresses to weaken the heart muscles and respiratory muscles (the muscles that help you breathe in and out).

Becker Muscular Dystrophy (BMD)

Becker MD begins with muscle loss in the hips, pelvis, thighs, and shoulders. BMD is basically a milder form of Duchenne MD. Symptoms include:

- Physical difficulties similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Waddling gait (the way a person walks), perhaps walking on toes or sticking out the abdomen to balance weak muscles

BMD progresses more slowly over the course of decades, and it is a milder and less predictable disease. Some men with BMD need wheelchairs by age 30 years or later; others manage for many years with minor aids, such as a walking cane.

If you think your child may have any form of MD, take your child to the doctor as soon as possible for diagnosis and comprehensive care.

Doctor Examination

To diagnose MD, your child's doctor will:

- Take a complete medical history of your child and the family

- Perform a thorough physical examination of your child

- Maybe order laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis of MD

Patient History

Your child's doctor will discuss your child's general health and past illnesses. Be sure to provide your child's complete medical history, including any other health problems. The doctor will also ask you to describe your child's symptoms.

During the appointment, tell the doctor if other family members have any signs or symptoms of MD. Also, be prepared to discuss the ages at which your child achieved growth milestones, such as learning how to walk.

Physical Examination

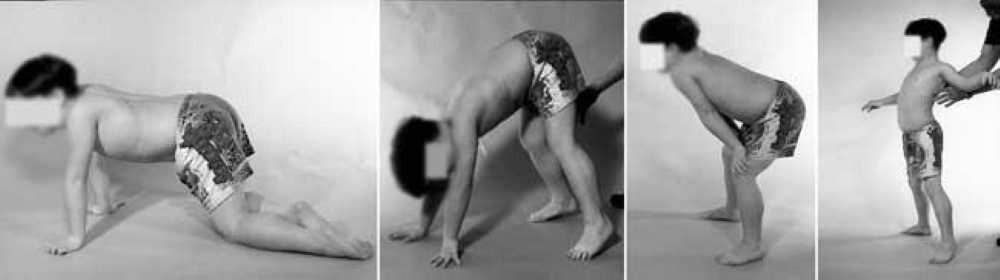

Your child's doctor will want to see how your child stands up from a sitting position on the floor. Because of weak leg muscles, children with DMD stand up in a unique way that has been termed the Gower's maneuver. They start out on their hands and feet, planting their feet widely apart and pushing up their bottom first. Then they use their hands to push up on their knees and thighs.

The doctor will also watch your child walk. They may carefully test your child's muscles and nervous system.

Laboratory Tests

Your child's doctor may use certain laboratory tests to confirm that your child has MD, or to monitor for changes caused by the disease:

- Blood tests. The doctor checks a blood sample for high levels of the enzyme creatine kinase, which can indicate muscle damage.

- Electromyography. The doctor puts small electrodes into muscle to measure electrical activity. Changes in the pattern of activity can show disease.

- Muscle biopsy. The doctor removes a small piece of muscle to study in the laboratory. This can distinguish various forms of MD from other muscle diseases.

- Genetic testing. Sometimes, the doctor can study a blood sample to identify an abnormal gene and diagnose MD.

- Bone mineral density. The bones of children can become weak over time, especially for children in wheelchairs. Your child's doctor might test bone density to determine if treatment is needed.

- Pulmonary function test. The doctor may monitor for changes in respiratory (breathing) function over time with a special breathing test.

Treatment

Doctors do not yet have a cure for any type of MD. Fortunately, timely treatment can help slow progression (worsening) of complications and maximize your child's quality of life.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The goals of nonsurgical treatment of MD include:

- Keeping your child's body flexible, upright, and mobile

- Helping your child function independently for as long as possible

Your child's doctor may recommend various nonsurgical treatments:

- Physical therapy and bracing to prevent contractures. The doctor may prescribe daily stretching exercises to improve your child's ability to walk. Regular, moderate physical therapy may help maintain range of motion in stiff joints (contractures). Walking braces for the ankle-foot or the knee-ankle-foot can help support weak muscles and keep the body flexible, slowing progression (worsening) of contractures.

- Medications. In recent years, the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of MD has been shown to be very beneficial — often extending the child’s ability to walk, as well as delaying, or avoiding, the onset (first signs) of scoliosis. Although corticosteroids have been proven effective in slowing muscle degeneration, these medications have side effects, and their use should be discussed thoroughly with your pediatric neurologist.

- Assistive devices. Rehabilitative devices such as canes, walkers, wheelchairs, strollers, and power wheelchairs can help maintain your child's mobility and independence. Sometimes it helps to make modifications (changes) to your home, such as widening doorways and installing (putting in) wheelchair ramps.

Surgical Treatment

Your child's doctor may recommend surgical procedures to help maintain your child's functional skills and improve quality of life.

- Surgical release of contractures. If contractures are severe, your child's doctor may recommend tendon release surgery. In this procedure, the surgeon lengthens the tendon to relieve the muscle tension. The tendon then heals at the longer length. Some surgeries can help the child continue to walk.

- Spinal fusion for scoliosis. The scoliosis curve in a wheelchair-dependent child with MD can become so severe that it further aggravates an already-present breathing problem. Having spine surgery before this happens can help with breathing function, lessen back pain, and improve sitting balance. All of these factors improve the child's quality of life. During a spinal fusion procedure, the curved portion of the spine is put in a straighter position and "fused" together using bone graft. Metal screws and rods are typically used to hold the spine in place while the bone graft fuses with the existing spinal bones.

Coping with Muscular Dystrophy

Like all children, those with MD need to feel loved, valued, and safe. They need to develop strong self-esteem. Parents, siblings, other family members, and friends can help by seeing the child first, not the disease.

Keep a positive attitude, communicate openly and honestly, and be patient and optimistic. Life expectancy (the number of years a person lives) is often shorter with muscular dystrophy, and it can be challenging living with the symptoms, but by giving your love, support, and encouragement, you can help your child have a happy and rewarding life.

Some tips for coping:

- Encourage your child to stay independent for as long as possible.

- Answer your child's questions about MD. Give an older child more information about the disease and allow them to take part in medical decision-making.

- Ask for and accept help from other people. Family members of people with MD face significant physical, emotional, and financial commitments.

- Consider joining a support group to learn coping strategies and to know that you are not alone.

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.