Diseases & Conditions

Distal Femur (Thighbone) Fractures of the Knee

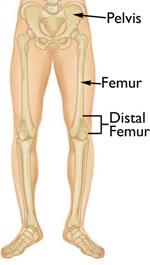

A fracture is a broken bone. Fractures of the thighbone that occur just above the knee joint are called distal femur fractures. The distal femur is where the thighbone flares out like an upside-down funnel.

Distal femur fractures most often occur either:

- In older people whose bones are weak, or

- In younger people who have high energy injuries, such as from a high-speed motor vehicle collision.

In both the elderly and the young, the breaks may extend into the knee joint and, in some cases, may shatter the bone into many pieces.

Anatomy

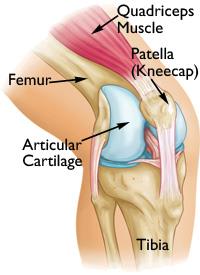

The knee is the largest weightbearing joint in your body. The distal femur makes up the top part of your knee joint. The upper part of the shinbone (tibia) supports the bottom part of your knee joint.

The ends of the femur are covered in a smooth, slippery substance called articular cartilage. This cartilage protects and cushions the bone when you bend and straighten your knee.

Strong muscles in the front of your thigh (quadriceps) and back of your thigh (hamstrings) support your knee joint and allow you to bend and straighten your knee.

Description

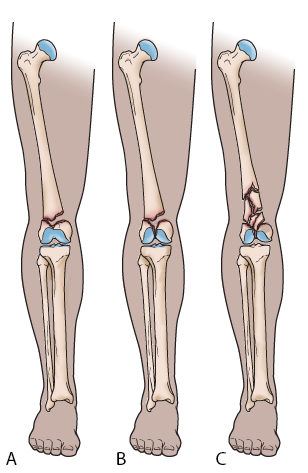

Distal femur fractures vary.

- The bone can break straight across (transverse fracture).

- The bone can break into many pieces (comminuted fracture).

- Sometimes these fractures extend into the knee joint and separate the surface of the bone into a few (or many) parts. These types of fractures are called intra-articular fractures. Because they damage the cartilage surface of the bone, intra-articular fractures can be more difficult to treat.

Distal femur fractures can be:

- Closed — meaning the skin is intact (not broken).

- Open — an open fracture is when a bone breaks in such a way that bone fragments stick out through the skin or a wound penetrates down to the broken bone. Open fractures often involve much more damage to the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments. They have a higher risk of complications and take a longer time to heal.

When the distal femur breaks, both the hamstrings and quadriceps muscles tend to contract and shorten. When this happens the bone fragments change position and become difficult to line up with a cast.

Cause

Fractures of the distal femur most commonly occur in two patient types: younger people (under age 50) and the elderly.

- Distal femur fractures in younger patients are usually caused by high-energy injuries, such as falls from significant heights, or motor vehicle collisions. Because of the forceful nature of these fractures, many patients also have other injuries, often of the head, chest, abdomen, pelvis, spine, and other limbs.

- Elderly people with distal femur fractures typically have poor bone quality. As people age, their bones get thinner. Bones can become very weak and fragile. A lower-force event, such as falling from a standing position or falling out of bed, can cause a distal femur fracture in an older person who has weak bones. Although these patients do not often have other injuries, they may have concerning medical problems, such as conditions of the heart, lungs, and kidneys, and/or diabetes. Learn more: Osteoporosis

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of distal femur fracture include:

- Pain with weightbearing

- Swelling and bruising

- Pain to touch over the thigh or knee

- Deformity — the knee may look "out of place," and the leg may appear shorter and crooked

In most cases, these symptoms occur around the knee, but you may also have symptoms in the thigh area.

Doctor Examination

Medical History

It is important for your doctor to know:

- The circumstances of your injury. For example, if you fell from a tree, how far did you fall?

- Whether you sustained any other injuries.

- Whether you have any other medical problems, such as diabetes.

- Whether you take any medications and, if so, the names of the medications, how often you take them, and how much you take (dosage). This includes both prescription and over-the-counter medications.

Physical Examination

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will do a careful examination. The will

- Assess your overall condition to make sure no other body parts have been injured (head, belly, chest, pelvis, spine, and other extremities)

- Examine your skin around the fracture to make sure it is not an open fracture

- Check the blood and nerve supply to your leg

Imaging Tests

Other tests that will provide your doctor with more information about your injury include:

- X-rays. The most common way to evaluate a fracture is with X-rays, which provide clear images of dense structures like bone. X-rays can show whether a bone is intact (whole) or broken. They can also show the type of fracture and where it is located within the femur. X-rays may also be taken of adjacent bones and joints (those next to or near the fracture) to look for other injuries.

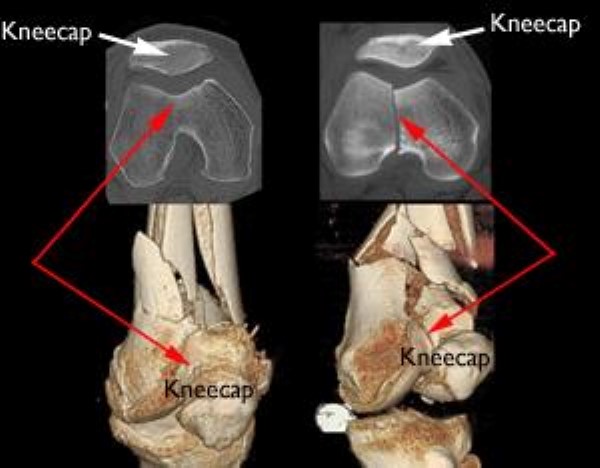

- Computed tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan shows a cross-sectional image of your limb. It can provide your doctor with valuable information about the severity of the fracture. This scan can show whether the fracture enters the joint surface and, if so, how many pieces of bone there are. A CT scan will help your doctor decide how to fix the break.

Other Tests

Your doctor may order other tests that do not involve the broken leg to make sure no other body parts are injured (head, chest, belly, pelvis, spine, arms, and other leg).

Sometimes, other tests are done to check the blood supply to your leg.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment options for distal femur fractures include:

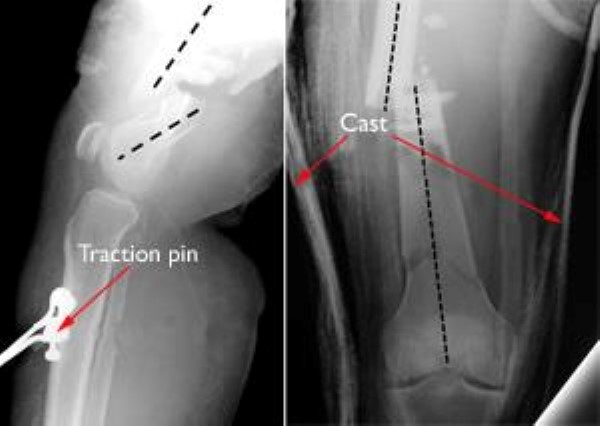

- Skeletal traction. Skeletal traction is a pulley system of weights and counterweights that holds the broken pieces of bone together. A pin is placed in a bone to position the leg.

- Casting and bracing. Casts and braces hold the bones in place while they heal. In many cases of distal femur fracture, however, a cast or brace cannot correctly line up the bone pieces because shortened muscles pull the pieces out of place. Only fractures that are limited to two parts and are stable and well aligned can be treated with a brace.

Patients of all ages with distal femoral fractures do best when they can be up and moving soon after treatment (such as moving from a bed to a chair, and walking). Treatment that allows early motion of the knee lessens the risk of knee stiffness, and prevents problems caused by extended bed rest, such as bed sores and blood clots.

Because traction, casting, and bracing do not allow for early knee movement, they are used less often than surgical treatments. Your doctor will talk with you about the best treatment option for you and your injury.

Surgical Treatment

Because of newer techniques and special materials, the results of surgical treatment are good, even in older patients who have poor bone quality.

Timing of surgery. Most distal femur fractures are not operated on right away — unless the skin around the fracture has been broken by the fractured bones (open fracture). Open fractures expose the fracture site to the environment and, therefore, carry an increased risk of infection. In this situation, surgery is typically performed more urgently.

Surgery is typically performed 1 to 3 days after the patient is initially seen by a doctor. This gives the surgical team time to develop a treatment plan and prepare the patient for surgery. During the time leading up to surgery, doctors will work to reduce the potential risks caused by any medical conditions a patient has. This will help to ensure that the surgery goes as well as possible.

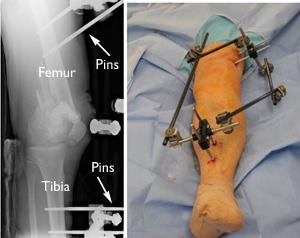

External fixation. If the soft tissues (skin and muscle) around your fracture are badly damaged, or if it will take time before you can tolerate a longer surgery because of health reasons, your doctor may apply a temporary external fixator. In this type of operation, metal pins or screws are placed into the middle of the femur and tibia (shinbone). The pins and screws are attached to a bar outside the skin. This device is a stabilizing frame that holds the bones in the proper position until you are ready for surgery.

When you are ready, your surgeon will remove the external fixator and place internal fixation devices on or in the bone under the skin and muscles.

Internal fixation. The internal fixation methods most surgeons use for distal femur fractures include:

- Intramedullary nailing. During this procedure, a specially designed metal rod is inserted into the marrow canal of the femur. The rod passes across the fracture to keep it in position.

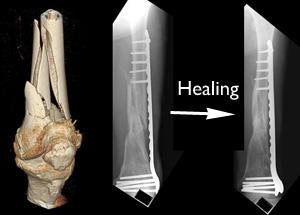

- Plates and screws. During this operation, the bone fragments are first repositioned (reduced) into their normal alignment. They are held together with screws and metal plates attached to the outer surface of the bone.

Both of these methods can be done through one large incision or several smaller ones, depending on the type of fracture you have and the device your surgeon uses.

If the fracture is in many small pieces above your knee joint, your surgeon will not try to piece the bone back together like a puzzle. Instead, your surgeon will fix a plate or rod at both ends of the fracture without touching the many small pieces. This will keep the overall shape and length of the bone correct while it heals. The individual pieces will then fill in with new bone, called a callous.

In cases where a fracture may be slow to heal, such as when a patient is elderly with poor bone quality, a bone graft may be used to help the callous develop. Bone grafts may be taken from the patient (most often from the pelvis) or from a tissue bank (cadaver bone). Other options include the use of artificial bone fillers.

In extreme cases, a fracture may be too complicated and the bone strength too poor to fix. These types of fractures are often treated by removing the fracture fragments and replacing the bone with a knee replacement implant.

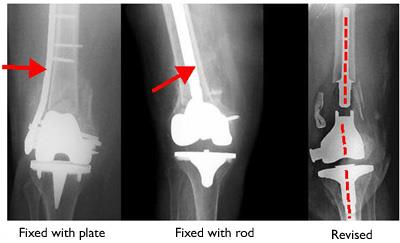

There is also the potential problem of distal femur fractures around existing knee replacements. As the population ages and the number of knee replacements rises, more distal femur fractures are being seen in those with knee replacements.

Fractures around knee replacements are typically treated with rods or plates, just like other distal femur fractures.

In rare cases, the existing knee replacement must be removed and replaced with a larger replacement. This procedure is called a revision and may be necessary if the implant is loose or not supported by surrounding healthy bone.

Learn more: Fracture After Total Knee Replacement

Surgical complications. To prevent infection, you will be given intravenous antibiotics before your procedure. Because blood clots in your leg veins may develop after surgery (deep vein thrombosis), your doctor may also give you blood thinners.

There will be blood loss during your surgery. In some cases, a blood transfusion may be helpful in your treatment. This will be discussed with you before your surgery.

Recovery

A distal femur fracture is a severe injury. Depending on several factors — such as your age, general health, and the type of fracture you have — it may take 1 year or more of rehabilitation before you are able to return to all everyday activities.

Pain Management

Pain after an injury or surgery is a natural part of the healing process. Your doctor and nurses will work to reduce your pain, which can help you recover faster.

Medications are often prescribed for short-term pain relief after surgery or an injury. Many types of medicines are available to help manage pain, including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. Your doctor may use a combination of these medications to improve pain relief, as well as minimize the need for opioids.

Be aware that although opioids help relieve pain after surgery or an injury, they are narcotics and can be addictive. Opioid dependency and overdose have become critical public health issues in the U.S. It is important to use opioids only as directed by your doctor and to stop taking them as your pain begins to improve. Talk to your doctor if your pain has not begun to improve within a few days of your treatment.

Early Motion

Your doctor will decide when it is best to begin moving your knee in order to prevent stiffness. This depends on how well the skin and muscle are recovering and how secure the fracture is after having been fixed.

Early motion sometimes starts with passive exercise of the knee, meaning a physical therapist will gently move your knee for you. The physical therapist will also instruct you on exercises to perform on your own.

If your bone was fractured in many pieces or your bone is weak, it may take longer to heal, and it may be a longer time before your doctor recommends motion activities.

Weightbearing

To avoid problems, it is very important to follow your doctor's instructions for putting weight on your injured leg.

- Some fractures may allow for weight to be placed on the injured leg, but it depends on the specific features of the fracture.

- These injuries frequently require a period with no weight placed on the leg, and it may take 3 months or more of healing before weightbearing can be done safely. During this time, you will need crutches or a walker to move around. You may also wear a knee brace for additional support.

- Your doctor will schedule regular X-rays to monitor how well your fracture is healing. If treated with a brace or cast, these regular X-rays show your doctor whether the fracture is lined up. Once your doctor determines that your fracture is stable enough, you can begin weightbearing activities. However, even though you can put weight on your leg, you may still need crutches or a walker at times as you recover your strength.

Rehabilitation

When you are allowed to put weight on your leg, it is very normal to feel weak, unsteady, and stiff. Even though this is expected, be sure to share your concerns with your doctor and physical therapist. A rehabilitation plan will be designed to help restore normal muscle strength, joint motion, and flexibility.

Your physical therapist is like a coach guiding you through your rehabilitation. Your commitment to physical therapy and making healthy choices can make a big difference in how well you recover.

To help you figure out how well your rehabilitation is going, as you recover, ask yourself:

- Is my ability to walk and care for myself improving?

- Are my normal activities of daily living improving?

- Is my pain gone or less, and are my knee motion, stability and strength improving?

The goals of rehabilitation are to get you and your knee back to normal function as much as possible. This may take up to 1 year or more.

Complications

Infection

Newer techniques in treating these difficult fractures have cut the infection rate by more than a half: Currently less than 5% of patients get infections after distal femur fractures. If you have surgery, your doctor will give you antibiotics to help prevent infection.

Open fractures (those with tears in the skin) and high-energy fractures (such as from a motor vehicle collision) have a higher risk for infection. If the infection is deep, it may involve the bone and the device used to fix the bone. A bone infection can require long-term, intravenous (IV) antibiotic treatment, as well as several surgeries to clean out the infection.

Learn more: Infection After Fracture

Stiffness

Some knee stiffness is expected after a distal femur fracture. Moving your knee soon after surgery is the best way to prevent stiffness. If you have lost significant knee motion and your fracture is healing, your doctor may suggest an additional operation to loosen up scar tissue around the kneecap.

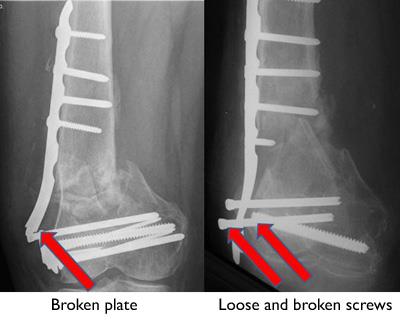

Bone Healing Problems

In some cases, bone healing can be slow (delayed union) or not happen at all (nonunion). If a follow-up X-ray shows rods, plates, and screws breaking or pulling out of the bone, it may be a sign that the bone is not healing. This can happen even if your fracture has been fixed well and you have followed your doctor's guidelines.

Open fractures and high-energy fractures are most at risk of not healing. These challenging fractures are also most at risk for infection, and infection can cause bone healing problems.

To help the fracture heal, your doctor may suggest applying a bone graft to the fracture, and changing or adding to how it was fixed (plates, screws, rods).

Knee Arthritis

Distal femur fractures that enter the knee joint may heal with a defect in the normally smooth surface of the joint. Because the knee is the largest weightbearing joint in the body, any defect can damage the protective articular cartilage and, over time, result in arthritis. In some cases, the joint surface may wear down to bare bone.

Arthritis caused by fracture or injury is called posttraumatic arthritis. It can be treated like other forms of osteoarthritis — with physical therapy, braces, medications, and lifestyle changes.

In cases of severe arthritis that limits activity, a total knee replacement may be the best option to relieve symptoms.

Long-Term Outcomes

It typically takes 1 year or more for a distal femur fracture to completely heal. Factors that may significantly affect healing and your long-term satisfaction include:

- How severe your injury is. Higher-energy fractures may be in more pieces and slower to heal, especially if they are open with more damage to soft tissues.

- Your bone quality. Better quality bone (younger patients) may keep the plates, screws, and rods better in place. Older patients and those with osteoporosis are at high risk for the implants loosening and pulling out of the bone. Newer techniques and implants may help prevent this risk but cannot eliminate it entirely.

- Your commitment to your recovery. Although recovery is a slow process, your commitment to physical therapy and following your doctor's guidelines are an essential part of your recovery and being able to return to the activities you enjoy.

Your doctor will regularly check how your recovery is progressing. They will assess:

- Your pain level (if any)

- Your leg strength

- Knee motion

- How well you are able to perform daily activities

Your satisfaction with doing normal everyday activities, as well as work and sports activities, is the final assessment of your recovery.

Contributed and/or Updated by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.