Diseases & Conditions

Congenital Scoliosis

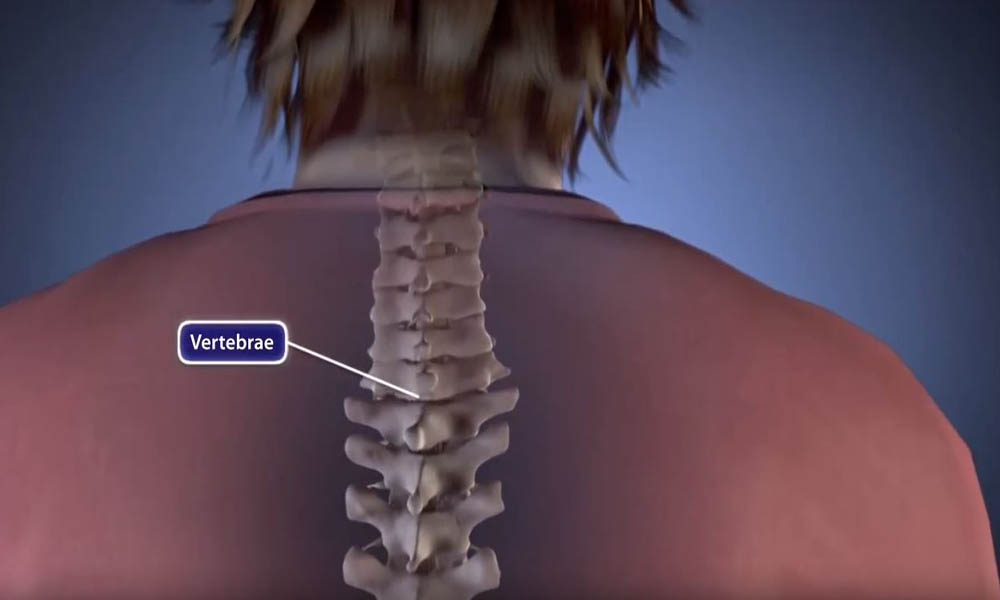

Congenital scoliosis is a sideways curvature of the spine that is caused by a defect that was present at birth. It occurs in only 1 in 10,000 newborns and is much less common than the type of scoliosis that begins in adolescence.

Children with congenital scoliosis sometimes have other health issues, such as kidney or bladder problems. They also have a higher likelihood of central nervous system abnormalities, like "tethered spinal cord."

Even though congenital scoliosis is present at birth, it is sometimes impossible to see any spine problems until a child reaches adolescence. Milder forms are sometimes diagnosed incidentally (by accident): for example, when a patient has a chest X-ray for another reason.

Types of Congenital Scoliosis

Incomplete Formation of Vertebrae

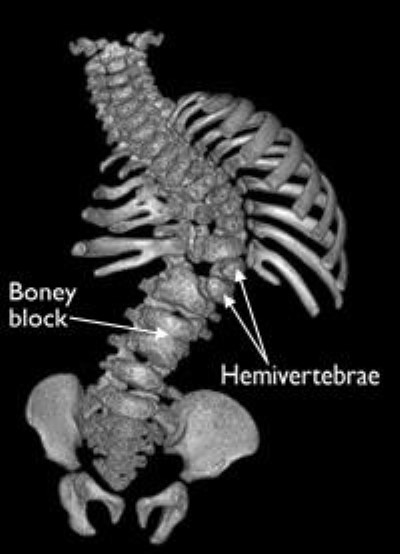

As the spine forms before birth, part of one vertebra (or more) may not form completely. When this occurs, the abnormality is called a hemivertebra (hemi = half), and it can produce a sharp angle in the spine. The angle can get worse as the child grows.

This abnormality can happen in just one vertebra or in many throughout the spine. When there is more than one hemivertebra, they will sometimes balance each other out and make the spine stable.

Failure of Separation of Vertebrae

During fetal development, the spine forms first as a single column of tissue that later separates into segments that become the bony vertebrae. If this separation is not complete, the result may be a partial fusion (bony bar) joining two or more vertebrae together.

Such a bar prevents the spine from growing fully.

- If the bar is large or on both sides of the vertebra, it can lead to a shorter but straight spine with fewer motion segments or joints.

- If the bar is present on only one side of the vertebra, this results in a spinal curve that increases as a child grows.

Combination of Bars and Hemivertebrae

The combination of a bar on one side of the spine and a hemivertebra on the other causes the most severe growth problem. These cases can require surgery at an early age to stop the increased curvature of the spine. Not having this surgery will result in severe scoliosis later in life.

Compensatory Curves

In addition to congenital scoliosis curves, a child's spine may also develop compensatory curves to maintain an upright posture. This means that the spine tries to make up (compensate) for a scoliosis curve by creating other curves in the opposite direction above or below the affected area. The vertebrae are shaped normally in compensatory curves.

Symptoms

Congenital scoliosis is often detected when a pediatrician examines the child at birth and notices a slight abnormality of the back. However, milder forms can be hard to see, and therefore go undetected, for years.

Scoliosis is not painful, so if the curvature is not discovered at birth, it can go undetected until there are obvious signs — which could be as late as adolescence. A child may suspect that something is wrong when clothes do not fit properly. Parents can discover the problem in early summer when they see their child in a bathing suit.

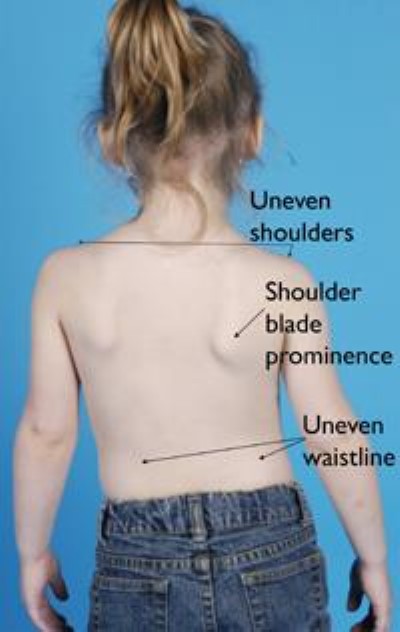

The physical signs of scoliosis include:

- Tilted, uneven shoulders, with one shoulder blade protruding (sticking out) more than the other

- Prominence of the ribs on one side (the ribs are more visible on one side)

- Uneven waistline

- One hip is higher than the other

- Overall appearance of leaning to the side

- In rare cases, a problem with the spinal cord or nerves that produces weakness, numbness, or a loss of coordination.

Doctor Examination and Investigation

Physical Examination

The standard screening test for scoliosis is the forward bending test. Your child will bend forward and the pediatrician will observe your child from the back, looking for a difference in the shape of the ribs on each side. A spinal deformity will be most noticeable when your child is in this position.

With your child standing upright, the doctor will:

- Check to see if the hips and shoulders are level

- Check that the position of the head is centered over the hips

- Check the movement of the spine in all directions

The doctor may check the strength in your child's legs and the reflexes in the abdomen and legs to rule out a spinal cord or nerve problem.

Tests

Although the forward bending test can detect scoliosis, it cannot detect the presence of congenital abnormalities. Imaging tests can provide more information.

X-rays. Images of your child's spine are taken from the back and the side. The X-rays will show the abnormal vertebra(e) and how severe the curve is.

Once your child's pediatrician makes the diagnosis of congenital scoliosis, your child will be referred to a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon for specialized care and further tests.

Computed tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan can provide a detailed image of your child's spine, showing the size, shape, and position of the vertebrae. To see the vertebrae better, your doctor may have a 3-D image made from the CT scan. This looks like a photograph of the bones.

Ultrasound. The doctor will do an ultrasound of your child's kidneys to detect any problems.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Because an MRI can evaluate soft tissues better than a CT scan, an MRI will be done to check for abnormalities of the spinal cord at least once for every patient. The age at which the child has an MRI depends on several factors, including:

- The severity of the scoliosis

- Other physical examination findings

- Whether the child requires sedation or anesthesia for the MRI

The doctor will talk to you about when your child should have the MRI.

Treatment

There are several treatment options for congenital scoliosis. In planning your child's treatment, the doctor will consider:

- The type, number, and location of vertebral abnormalities

- The severity of the curve

- Any other health problems your child has

Your doctor will determine how likely it is that your child's curve will get worse, and then suggest treatment options to meet your child's specific needs.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Observation. A child with a small curve that seems to be unchanging will be monitored to make sure the curve is not getting worse. Although it does not happen in every patient, congenital scoliosis curves can get bigger as the spine grows and the deformity of the back becomes more noticeable. It is likely that a curve in a young child will get worse because younger children still have a lot of growing to do.

Your doctor will follow the changes of your child's curve using X-rays taken at 6- to 12- month intervals during the growing years.

Physical activity does not increase the risk for curve progression. Children with congenital scoliosis can participate in most sports and hobbies. Some restrictions may be suggested if your child has congenital abnormalities in the cervical spine (neck).

Bracing or casting. Braces or casts are not effective in treating the curvature caused by the congenitally abnormal vertebrae, but they are sometimes used to control compensatory curves where the vertebrae are normally shaped.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is reserved for patients who:

- Have curves that have significantly worsened during the course of X-ray monitoring

- Have or are expected to eventually have severe curves

- Have a large deformity of the spine or trunk

- Are developing a neurological problem due to an abnormality in the spinal cord

An important goal of surgery is to allow the spine and chest to grow as much as possible. There are several surgical options.

Spinal fusion. In this procedure, the abnormal curved vertebrae are fused together so that they heal into a single, solid bone. This will stop growth completely in the abnormal segment of the spine and prevent the curve from getting worse.

Hemivertebra removal. A single hemivertebra can be surgically removed. The partial correction of the curve that is achieved by doing this can then be maintained using metal implants. This procedure will only fuse two to three vertebrae together.

Growing rod. Growing rods do not actually grow on their own. They are lengthened by the doctor with minor surgery that is repeated over time.

The goal of a growing rod is to allow continued growth in height of the spine while correcting the curve. One or two rods are attached to the spine above and below the curve. Every 6 to 12 months, the child returns to the doctor, and the rod is lengthened to keep up with the child's growth.

When the child is fully grown, the rod(s) are replaced with "permanent" rods, and a spinal fusion is performed.

Newer technologies like magnetic, "spring-based," and ratcheted rods are emerging that limit the total number of surgeries a child must have. The selection of these implants depends on many factors, including the shape and length of the scoliosis and FDA approval (in the U.S.).

Recovery. While each child is different, in general:

- Young children usually recover quickly from surgery and are discharged from the hospital within 3 to 7 days.

- Depending on the operation, the child may need to wear a cast or brace for 3 to 4 months.

- Once they are healed, children are allowed to participate in most of the activities that they had previously participated in.

Long-Term Outcomes

Congenital scoliosis detected at an early age is one of the most challenging types of scoliosis to treat. The curves can be large to begin with and because children have so much growth ahead of them, the chance of severe curvature is high.

Although fusion of vertebrae at an early age results in the spine and trunk being shorter than they would have been, children can have outstanding results and achieve normal, or near-normal, function. This is sometimes a good option to avoid multiple surgeries.

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.