Diseases & Conditions

Adult Spondylolisthesis of the Low Back

In spondylolisthesis, one of the bones in your spine — called a vertebra — slips forward and out of place. This may occur anywhere along the spine, but is most common in the lower back (lumbar spine). In some people, this causes no symptoms at all. Others may have back pain or leg pain that ranges from mild to severe.

Understanding how your spine works can help you better understand spondylolisthesis. Learn more about spine anatomy at Spine Basics.

Anatomy

The spine is made up of small bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another and create the natural curves of the back. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. They act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Description

Spondylolisthesis occurs when one of the vertebrae in the spine slips forward and out of place. This creates instability in the spine, can cause pain, and can also accelerate the formation of bone spurs (which are outgrowths)/arthritis.

Cause

There are several causes/types of spondylolisthesis. The two most common types in adults are degenerative and spondylotic/congenital.

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

As we age, general wear and tear causes changes in the spine.

- The intervertebral disks in the spine lose height, become stiff, and begin to dry out, weaken, and bulge.

- As these disks lose height, the ligaments and joints that hold our vertebrae in proper position begin to weaken. In some people, this can create instability and ultimately result in degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS).

- As the spine continues to degenerate, the ligaments along the back of the spine may begin to buckle, which can result in nerve compression.

- As the slippage in the spine worsens, the spinal canal can also become narrowed. Ultimately, this narrowing and buckling can lead to compression of the spinal cord (spinal stenosis). Spinal stenosis is a common problem in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Women are more likely than men to have degenerative spondylolisthesis, and it is more common in patients over the age of 50. A higher incidence has been noted in the African-American population than in other populations.

Spondylolytic Spondylolisthesis (Isthmic Spondylolisthesis)

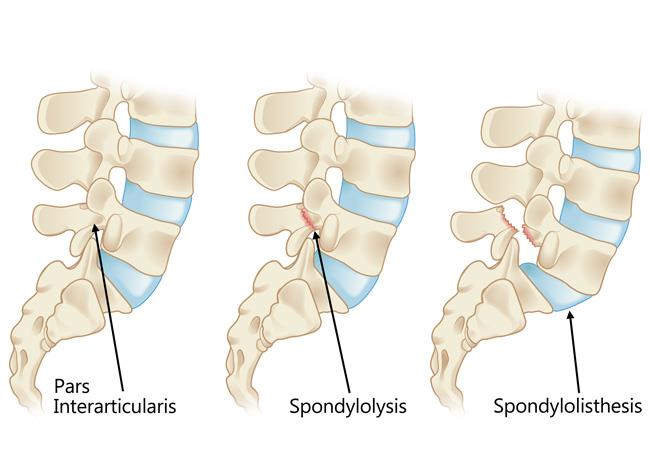

Another common cause of spondylolisthesis is a stress fracture (a crack from inadequate bone) in the vertebra. The fracture typically occurs in an area of the lumbar (lower) spine called the pars interarticularis. This type of spondylolisthesis is called isthmic spondylolisthesis.

- In most cases of isthmic spondylolisthesis, the pars fracture (also called spondylolysis) occurs during adolescence and goes unnoticed until adulthood.

- The normal disk degeneration that occurs in adulthood can then stress the pars fracture and cause the vertebra to slip forward. The stress fracture does not always cause the slip to occur, and very rarely does the slip progress significantly and get worse over time. Symptoms of isthmic spondylolisthesis often begin in middle age.

- Because a pars fracture causes the front (vertebra) and back (lamina) parts of the spinal bone to disconnect, only the front part slips forward. This means that narrowing of the spinal canal is less likely than in other kinds of spondylolisthesis, such as DS (in which the entire spinal bone slips forward).

- However, as patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis age, spinal stenosis can occur just as in degenerative spondylolisthesis, causing bone spurs to narrow the spinal canal and result in nerve compression.

About 4% to 6% of the U.S. population has spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

Symptoms

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis will often develop leg and/or lower back pain when slippage of the vertebrae begins to put pressure on the spinal nerves. The most common symptom in the legs is a feeling of widespread weakness when you stand or walk for a long time.

Leg symptoms may be accompanied by numbness, tingling, and/or pain that is often affected by posture.

- Forward bending or sitting often relieves the symptoms because it opens up space in the spinal canal.

- Standing or walking often increases symptoms.

Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Most people with isthmic spondylolisthesis have low back pain, which they believe is activity-related. The back pain is sometimes accompanied by leg pain. In elderly patients, isthmic spondylolisthesis can also be accompanied by symptoms of spinal stenosis.

Doctor Examination

Doctors use the same tools to diagnose both degenerative spondylolisthesis and isthmic spondylolisthesis.

Medical History and Physical Examination

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your back. This will include looking at your back and push on different areas to see if it hurts. Your doctor may have you bend forward, backward, and side-to-side to see if you pain or if movement is limited.

Imaging Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to help confirm your diagnosis. These include:

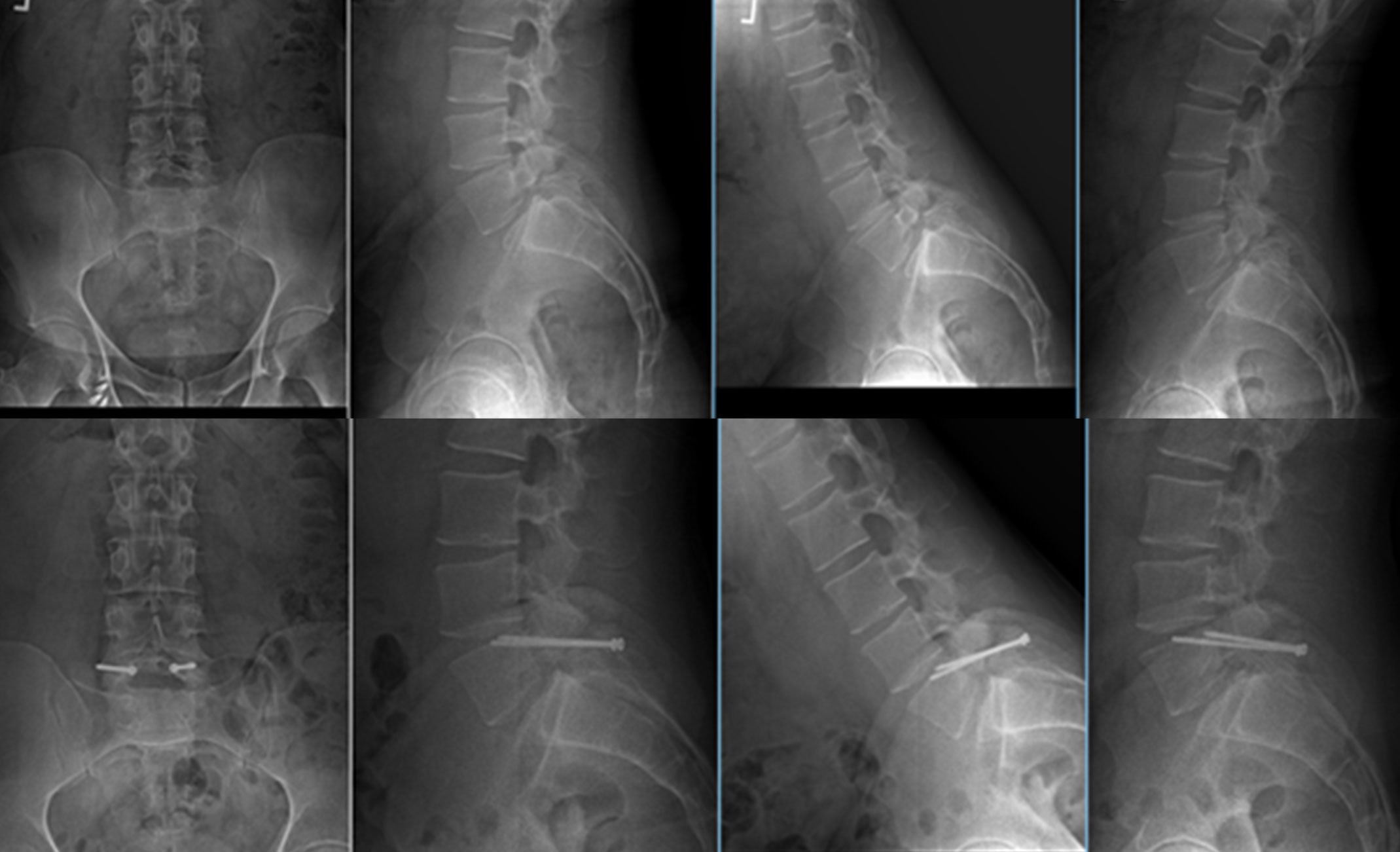

X-rays. X-rays visualize bones and will show whether a lumbar vertebra has slipped forward. They will also show changes that occur with aging, such as loss of disk height or bone spurs.

Flexion-extension X-rays — taken while you lean forward and backward — can show instability or too much movement in your spine.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI scans provide images of soft tissues, such as muscles, disks, nerves, and the spinal cord. They can show the vertebra slippage in more detail and whether any of the nerves are pinched.

Computed tomography (CT). CT scans create three-dimensional cross-section images of your spine and help doctors clearly see the bony structures.

If you are unable to have an MRI scan because of an associated medical condition, your doctor may order a CT myelogram. In this test, a radiologist will inject dye into your spinal canal. Then, before taking the CT scan, the radiologist may have you lie on a table that moves around so the dye can spread inside the spinal canal.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Although nonsurgical treatments will not repair the vertebral slippage, many patients report that these methods help relieve symptoms.

Physical therapy and exercise. Specific exercises can strengthen and stretch your lower back and abdominal muscles.

Medication. Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen, may relieve pain.

Steroid injections. Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory. Cortisone injected around the nerves or in the outermost part of the spinal canal (epidural space) can decrease swelling, as well as pain. Cortisone injections are likely to decrease pain and numbness, but not weakness of the legs. Patients should not receive cortisone injections more than a few times per year.

Surgical Treatment

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis. If you have degenerative spondylolisthesis and your symptoms have not improved after 3 to 6 months of nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may recommend surgery, especially if you are unable to walk or stand and the pain and weakness negatively affect your quality of life.

To determine your surgical options, your surgeon will consider the extent of arthritis in your spine and whether there is too much movement in your spine.

Surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis has two goals:

- To relieve nerve compression

- To prevent or treat instability

In most cases, relieving nerve compression is the top priority. This is typically achieved with laminectomy — a procedure during which your surgeon removes the bone spurs and thickened ligaments that are causing nerve compression.

Sometimes, your surgeon may be able to indirectly decompress your spine using other surgical methods.

If your surgeon believes your spine is stable enough, you may not need to have it stabilized with a spinal fusion.

Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. If you have isthmic spondylolisthesis and your symptoms have not improved after 6 to 12 months of nonsurgical treatment, you may be a candidate for surgery. Surgery may also be a good option if you have:

- Worsening neurologic symptoms, such as weakness, numbness, or frequent falls

- Symptoms of damage to the nerves below the end of the spinal cord (cauda equina syndrome)

The main goal of surgery for isthmic spondylolisthesis is to stabilize the spine, and it can be accomplished with either pars repair or spinal fusion.

Pars Repair

In patients who do not have significant degenerative changes, pars repair is a motion-preserving alternative to spinal fusion.

- During pars repair, the surgeon places screws only in the fractured vertebra. Because the disks and facet joints above and below the fracture remain intact, patients who undergo pars repair keep the natural flexibility of their spine.

- Over time, the pars fracture heals much like a broken bone would. Once the fracture heals, the spine is both stable — giving the patient significant pain relief — and can move normally.

If you have significant nerve compression, your surgeon may choose to decompress the nerves at the same time, with a procedure called a foraminotomy.

Spinal Fusion

In patients who have substantial degenerative changes, spinal fusion is usually performed.

Fusion is a welding process that typically uses screws and rods to fuse together two or more vertebrae into a single, solid bone. This stops the motion in the unstable level.

If you also have nerve compression, your surgeon may choose to decompress the spine through a laminectomy.

Recovery

Recovery from a laminectomy without fusion may take only 1 to 2 months because the bones do not have to fuse.

Pars repair and fusion recovery both take more time. It may be several months before the bone is solid, although your comfort level will often improve quickly. Immobilization with a brace is often initially recommended.

For more information about spinal fusion and recovery: Spinal Fusion

Conclusion

Nonsurgical treatment is successful in most degenerative spondylolisthesis and isthmic spondylolisthesis patients. When surgery is indicated, successful clinical outcomes have been reported in more than 85% of patients.

In addition, results from the largest clinical trial on spine patient outcomes revealed that patients who were treated surgically maintained substantially greater pain relief and improvement of function than patients who were treated nonsurgically.

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.