Treatment

Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion

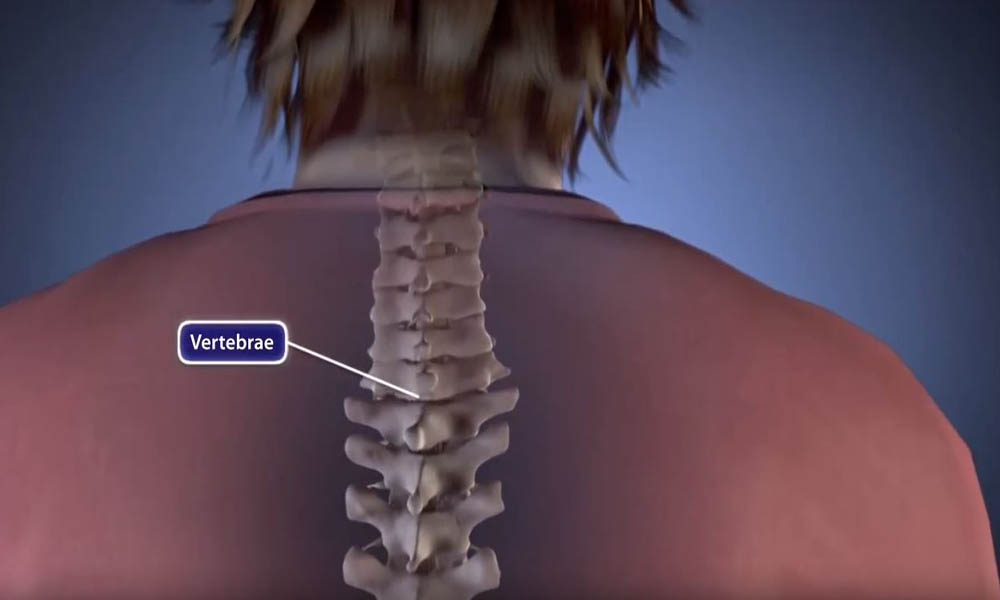

Spinal fusion is a surgical procedure used to correct problems with the small bones in the spine (vertebrae). It is essentially a welding process. The basic idea is to fuse together the painful vertebrae, so they heal into a single, solid bone.

Spinal fusion is a treatment option when motion is the source of pain — the theory being that if the painful vertebrae do not move, they should not hurt.

This article focuses on one method of fusing the lumbar (lower) spine — lateral lumbar interbody fusion — and discusses just the surgical component of the procedure. For a complete overview of spinal fusion, including approaches, bone grafting, complications, and rehabilitation, please refer to Spinal Fusion.

Interbody Fusion

An interbody fusion is a type of spinal fusion that involves removing the intervertebral disk from the disk space.

When the disk space has been cleared out, your surgeon will implant a metal, plastic, or bone spacer between the two adjoining vertebrae. This spacer, or cage:

- Promotes bone healing

- Helps make the fusion happen

- Increases the collapsed intervertebral disk space.

After the cage is placed in the disk space, the surgeon may add stability to your spine by using metal screws, plates, and rods to hold the cage in place.

Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion

An interbody fusion can be performed using a variety of different approaches. For example, a surgeon can access the spine through incisions in the lower back or through incisions in the side of the body.

In a lateral lumbar interbody fusion, the surgeon takes a side approach and centers the incision over the patient's flank. With this approach, the surgeon can reach the vertebrae and intervertebral disks without moving the nerves or opening up muscles in the back.

The lateral approach is often referred to as extreme lateral or direct lateral interbody fusion (XLIF or DLIF). The surgeon accesses the spine by going through the psoas muscle, the muscle that enables the hip to flex, rotate, and adduct (move toward the midline of the body).

A separate lateral approach, referred to an anterolateral interbody fusion (OLIF or ATP) is similar to a direct lateral interbody fusion, except the psoas is not typically disrupted. The surgeon accesses the spine by going in front of the psoas, and places the interbody fusion cage at an angle. This technique can theoretically decrease the risk of nerve damage and muscle pain, but there is a slightly higher risk of blood vessel and bladder injury.

Surgical Technique

For the surgery, the patient is placed in the side position, and the operating table is bent to provide the surgeon with an optimal view of the spine.

In some cases, the surgeon inserts an instrument called a tubular retractor through the skin and soft tissues down to the spinal column. The tubular retractor holds the muscles open and gives the surgeon a clear view of the spine.

During the procedure, the surgeon removes the disk and inserts a cage packed with bone graft between the vertebrae. Often, titanium screws are used to hold the cage in place, inserted through an additional incision on the back.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion

Each surgical approach — whether from the front, back, or side — has advantages and disadvantages. The potential advantages of a lateral lumbar fusion include:

- Less damage to the midline back muscles

- Easier access to the spine, in many cases

- Improved alignment of the spinal bones

- Avoiding previous scar tissue if the patient has had previous lumbar surgery

In addition, a lateral fusion may be performed with a less invasive technique, resulting in reduced muscle injury.

These results can also be achieved through fusions performed from the back or the front.

Typically, the complication rate for the lateral procedure is lower than for traditional spinal surgery. Possible disadvantages include:

- Anterior thigh pain, which is usually temporary

- Nerve damage, which can result in weakness in lifting up the leg

- Rare incidence of bowel, bladder, or blood vessel injury (<0.1%)

- Incisional hernia (where the muscle seems to pouch out)

- Hematoma, or bleeding into the psoas muscle, which typically goes away on its own

Talk to your surgeon about the approach that will best meet your health needs.

Recovery

Patients typically go home the same day or next day if only one level is fused. If more than one level is fused, most patients stay overnight.

After going home, patients should watch for any belly pain or weakness in the legs that make their legs buckle and alert the surgeon right away if these symptoms occur.

Pain medication is usually needed for a few days to weeks. Your surgeon may also provide you with a brace to help the fusion heal.

Outcomes for lateral lumbar interbody fusion are equivalent to those of traditional surgeries. Because this procedure is performed through a smaller incision, it may minimize muscle damage.

Future Directions

Newer technology has led to the development of cages made of different materials, which can be used to improve the fusion rate. In addition, expandable cage technology is being used to insert smaller devices which can then expand to fit your anatomy. Using a smaller cage may reduce the risk of muscle and nerve damage.

Finally, surgeons are commonly using a different variation of the lateral procedure called the prone lateral technique, in which the patient is positioned on their stomach, and the disk space is accessed in a similar fashion to a direct lateral approach. The benefit to this procedure is that it reduces repositioning of the patient, which can decrease operative time. However, research has yet to determine if a prone lateral approach is riskier than a direct lateral approach, and it can be a more technically demanding procedure.

Last Reviewed

February 2023

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.