Treatment

Cubital Tunnel Release

Cubital tunnel release is a surgical procedure used to treat cubital tunnel syndrome (also known as ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow).

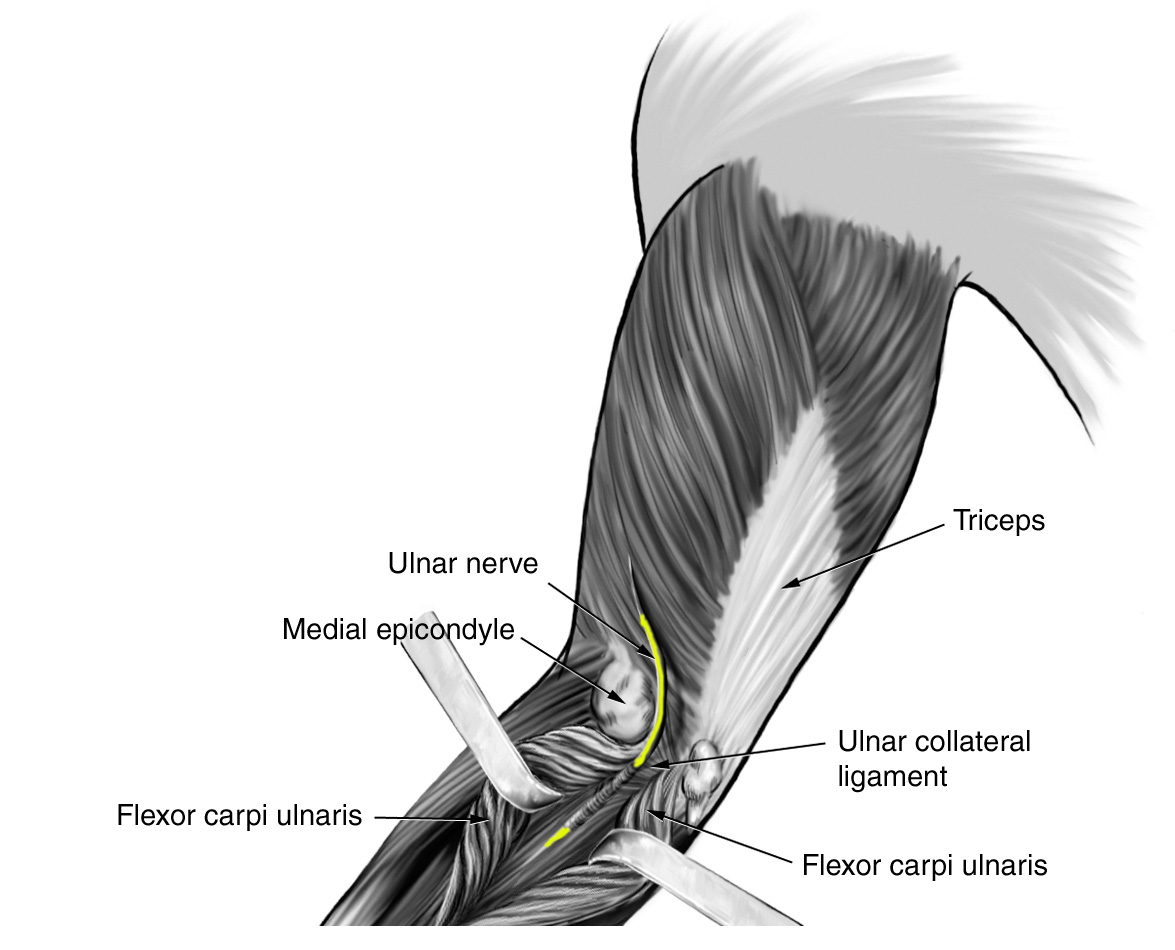

Patients with cubital tunnel syndrome have a pinched nerve at their elbow (ulnar nerve) and typically complain of numbness in the small finger and sometimes the ring finger. In severe cases, patients also have weakness in the muscles of the hand resulting in poor hand function.

- In milder cases that have only affected the patient for a few months, cubital tunnel release can improve and even reverse these symptoms.

- In severe cases that have plagued the patient for many months or years, surgery may prevent worsening symptoms but is less likely to reverse them.

When Is Cubital Tunnel Release Recommended?

In many cases, your doctor will recommend nonsurgical treatments before considering surgery. This may include splinting the elbow straight at night and learning exercises to help get the nerve moving better behind the elbow.

If your doctor believes your condition is too severe for nonsurgical treatment to be effective, or if you try nonsurgical treatments for a period of time and they do not work, surgery is the recommended next step.

Preparing for the Procedure

A variety of tests may be done prior to surgery, including:

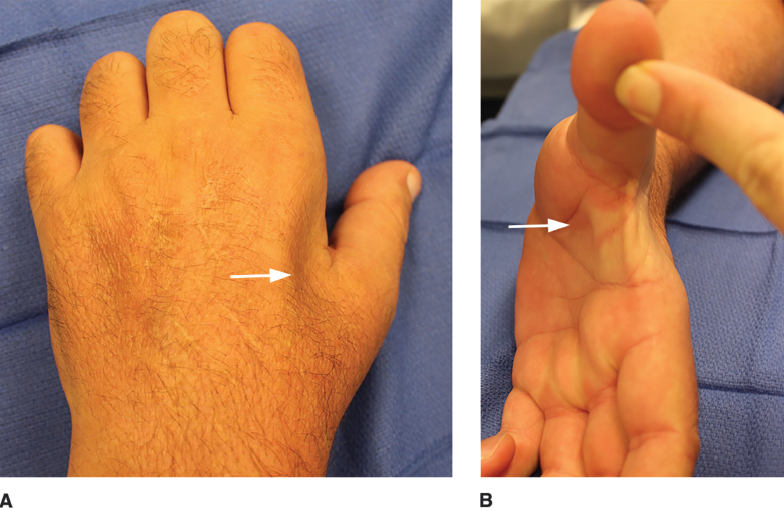

- Nerve Conduction Studies/EMG — electrical tests that can help confirm the presence of cubital tunnel syndrome and define how severe it is

- Ultrasound — an alternative to nerve conduction studies that can also confirm the diagnosis

In the weeks leading up to surgery:

- Avoid injury to the skin over the elbow. If a wound is present over the surgical site prior to the operation, the procedure may be delayed to avoid infection.

- If you are diabetic, you will often be encouraged to keep your blood sugar control as tight as possible. This reduces the risk of post-operative infection and wound healing issues.

- Smokers will typically be encouraged to avoid smoking for several weeks prior to the surgery also to reduce the risk of infections and wound complications. Learn more: Orthopaedic Surgery and Smoking

You should expect to be sore after surgery for several days. Thus, you should make arrangements at home and at work to account for this.

- People with sedentary jobs (e.g., working at a computer) may be able to return to work just a few days after surgery.

- People who have physically demanding jobs or activities (e.g., athletes, construction workers) will likely need to take 2 to 4 weeks off after surgery to allow their wounds to heal. This should be addressed ahead of time with your employer, teacher, coach, etc.

Procedure

Anesthesia

For the surgery, the patient is often given anesthesia to make them sleepy (general anesthesia), and the surgical site is numbed with medication (local anesthesia).

Sometimes, the entire arm may be numbed by an anesthesiologist in a procedure known as a "block." This leads to excellent pain control during and after the surgery in many cases.

Most surgeons will apply a tourniquet to the arm to prevent bleeding during the surgery. However, some surgeons will keep the patient awake during the surgery and use a cocktail of numbing medicine and blood vessel constricting medicine to provide pain control and prevent bleeding during the surgery, eliminating the need for a tourniquet. This is called wide awake local anesthesia no torniquet (WALANT) surgery.

Surgical Technique

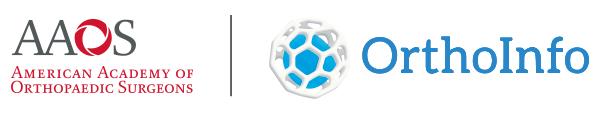

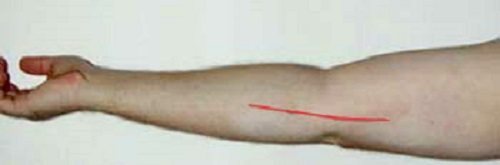

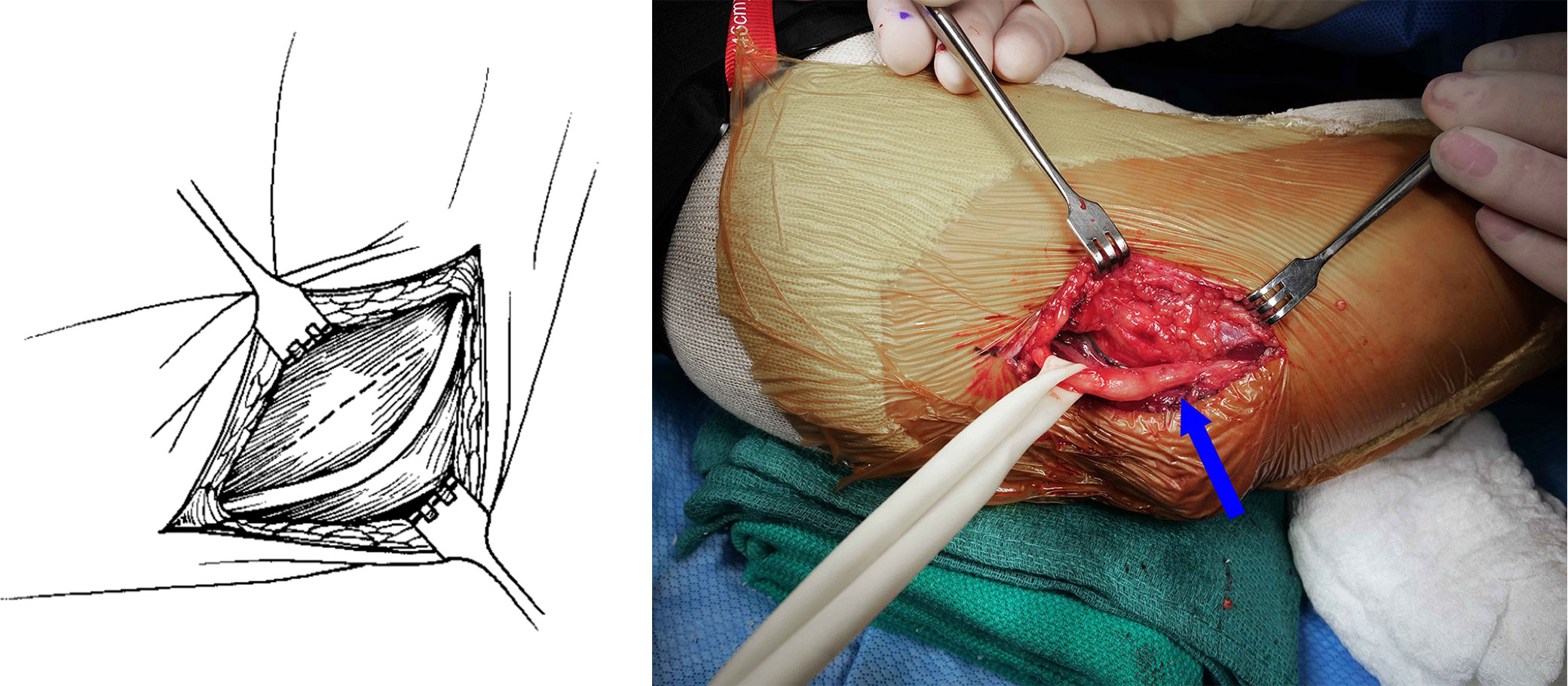

In an open procedure, which is the most commonly performed cubital tunnel surgery:

- The surgeon identifies the strong tissue (Osborne's ligament) known as fascia. All of the tissue on top of this fascia is carefully cleared away to give the surgeon a good view.

- The surgeon uses scissors to carefully open the fascia along the length of the incision.

- Once the nerve is completely released, the surgeon inspects it for damage.

- The surgeon then flexes and extends the elbow to make sure the nerve stays in the right spot. Surgery can cause the nerve to become unstable and jump over the elbow bone when the elbow moves, which is known as ulnar nerve subluxation. If this happens, the surgeon may move the nerve in front of the bone so the nerve stays in place when the patient moves their elbow. The technique to do this is called a "transposition" of the ulnar nerve. Transposition may be also done in patients with very severe compression of the nerve or patients who previously had cubital tunnel surgery and did not get better.

In total, this procedure takes around 20 to 40 minutes. It is almost always done on an outpatient basis, meaning the patient gets to go home after surgery and does not have to stay overnight in the hospital.

Recovery

- After surgery, you will feel groggy from the anesthesia and should be driven home by a family member or friend. You will need some rest as the anesthesia wears off.

- If a block was used, your arm will be numb and weak. You may be given a sling in the recovery area to use until strength returns, which can take a few hours.

- The pain after surgery may not start for a few hours due to the numbing medication/block given for the procedure.

Medications

- You may be sent home with prescription pain medicine, which can be used for pain the first few days after surgery. Many patients find that acetaminophen and ibuprofen are enough and do not need narcotic medications (such as opioids). If you do require narcotics, try to come off of them as soon as possible, as these medications are highly addictive.

- Antibiotics are not commonly needed after surgery and will not be prescribed in most instances.

Dressings and Wound Care

- The dressing is commonly left on for 5 to 7 days after surgery to keep the wound sterile. After this time, you can remove the bandage and shower.

- Clean and running water is safe at this time; however, the wound should not be submerged in stagnant water, such as an ocean, lake, pool, or hot tub for about 30 days after surgery.

- If a splint was applied after surgery, you should leave it on until instructed by your doctor.

Return to Activity

As mentioned above, patients with sedentary professions may feel up to returning to work a few days after surgery. Those with labor-intensive positions may need a few weeks off from work.

Complications

Complications from surgery can include:

- Infection

- Wound healing issues

- Injuries to nearby structures such as nerves/vessels/tendons

- Lack of improvement after surgery

- Worsening of the condition after surgery

Many patients complain of numbness over the tip of the elbow after surgery. This is due to irritation of a nerve that crosses the surgery site known as the medial antebrachial cutaneous (MABC) nerve. While this nerve can be accidentally cut during surgery, more commonly the nerve is simply irritated by the operation, and the numbness will go away over time.

Ulnar nerve subluxation — when the ulnar nerve jumps over the elbow bone during elbow movement — is usually detected and treated during the surgery (with a transposition). If not, it can be a nuisance and may require a return to the operating room.

The ulnar nerve itself can be injured during surgery. This is a difficult problem that can result in worsening symptoms, pain, and hand dysfunction. If this rare complication occurs, it may require further surgery.

Outcomes

Because the nerve injury/pinch is so far away from where the nerve branches power the hand and give sensation to the fingers, it can take awhile to see results from the surgery. Many surgeons caution their patients that it can take 12 to 18 months after surgery to see the final results.

Overall, long-term outcomes of cubital tunnel release are good. This is especially true in patients who have had milder disease over a shorter period of time.

- In some really severe cases of cubital tunnel syndrome, surgery will prevent worsening of symptoms but will not result in improved symptoms.

- Recurrent cubital tunnel syndrome — where symptoms go away after surgery and then come back — is rare. When it does happen, it commonly occurs years after surgery. In those cases, repeat surgery may be needed.

- In patients with hand weakness, surgery may or may not improve strength in the hand. Once muscle is lost, it does not tend to regenerate (grow back). Thus, it is important to seek treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome sooner rather than later to maximize the ability of the surgery to yield a good result.

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.