Diseases & Conditions

Sprained Finger

- When you fall onto an outstretched hand.

- When the finger is forced to the side or hit on end (i.e., "jammed"), such as while catching a ball

Anatomy

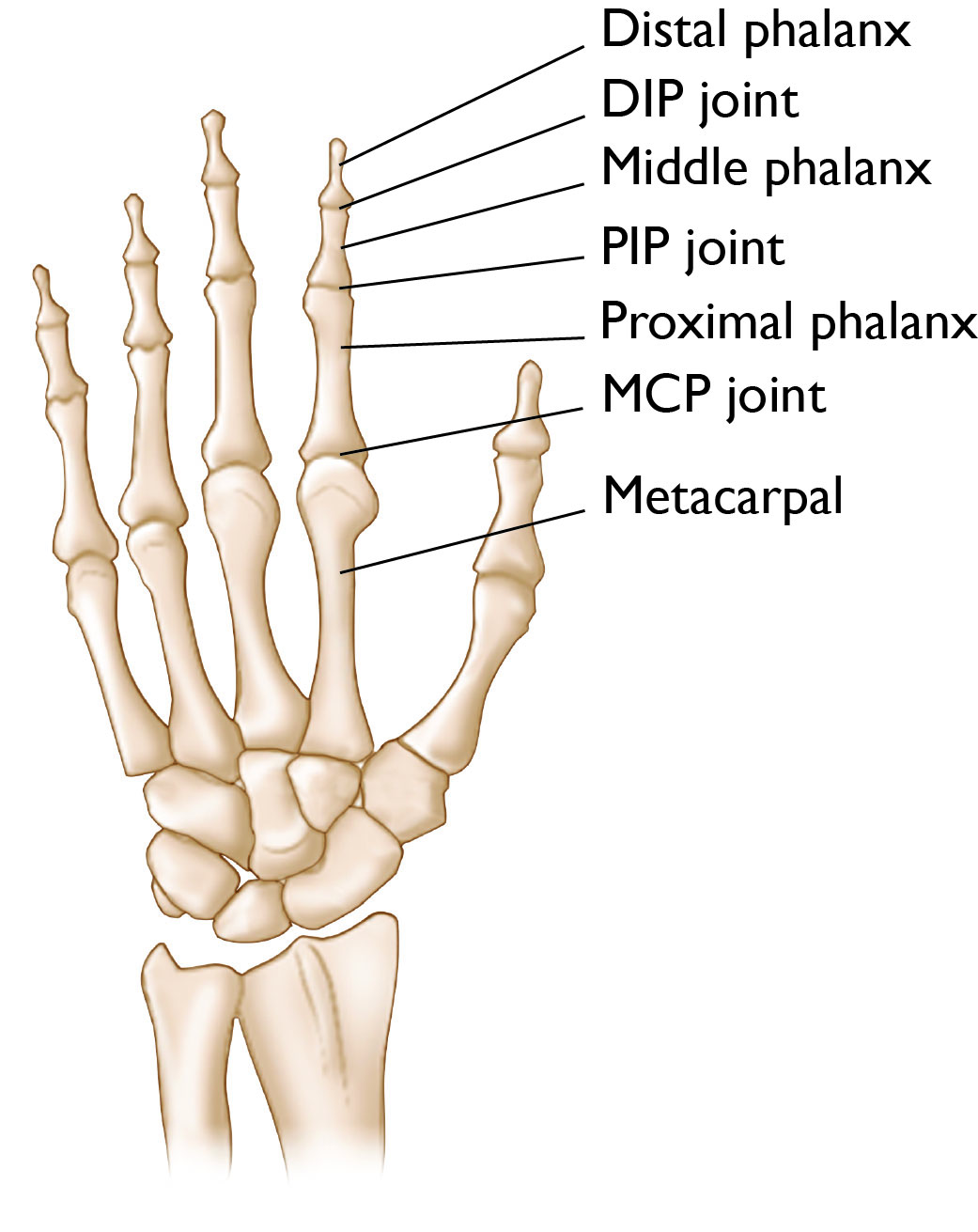

- The distal phalanx is the last bone of the finger at the very tip. It connects to the middle phalanx, the middle bone of the finger, via the DIP joint.

- The middle phalanx connects to the proximal phalanx, the bone in the finger closest to the hand, via the PIP joint.

- The proximal phalanx connects the finger to the hand (metacarpal) via the MCP joint.

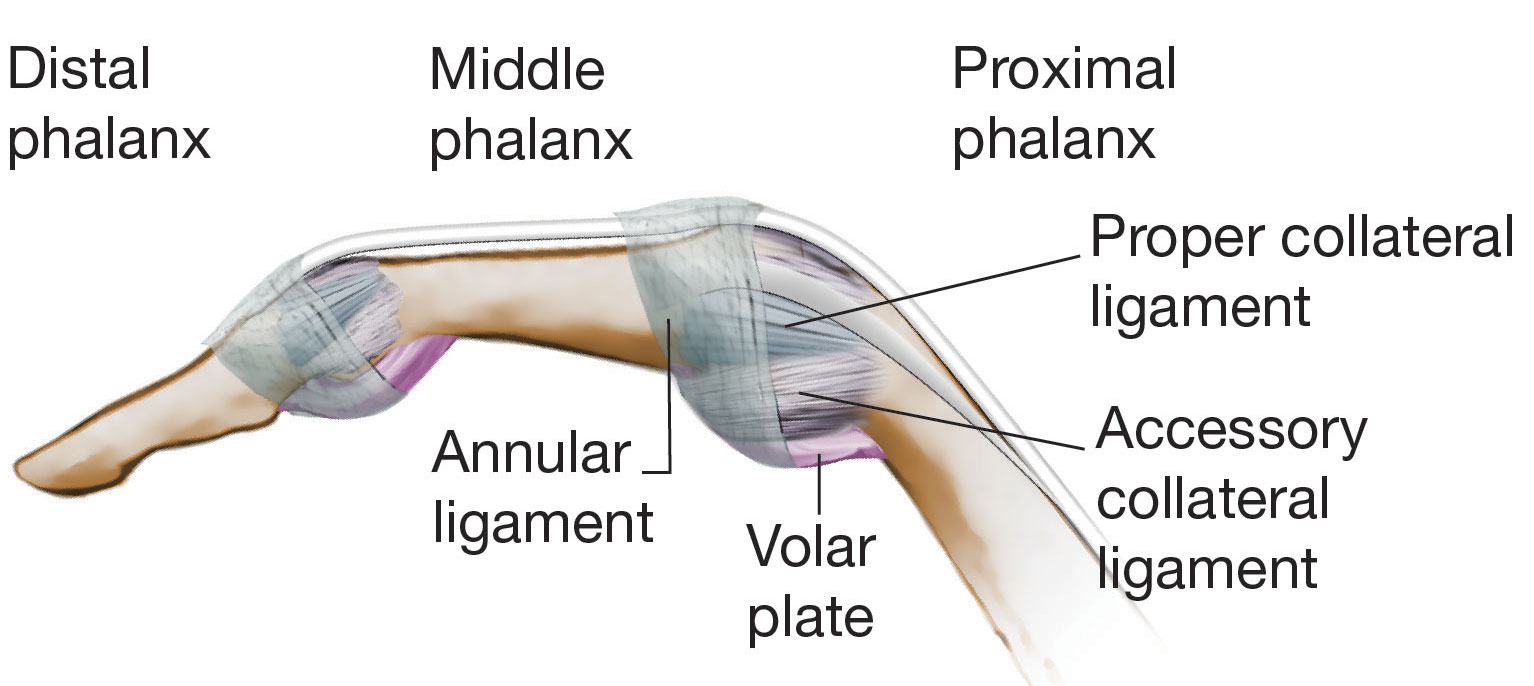

While each of these joints is slightly different from the others, they share several similarities.

- On the sides of each finger are collateral ligaments. Ligaments are strong, fibrous tissues that typically connect bones to other bones. The ligaments in the finger help keep the bones in proper position while allowing for motion at the joints.

- On the palm-side of each finger joint is a strong thick structure called the volar plate.

- Surrounding each finger joint is a structure called the joint capsule.

Description

- An injury to this joint typically causes pain and swelling.

- In severe cases, it may make the joint unstable.

- Following a sprain, the finger typically becomes stiff, and it can be hard to completely flex the finger (i.e., make a fist) and extend the finger (i.e., extend or straighten the finger).

Grades of Finger Sprains

- In the middle of the ligament, or

- At the end(s) of the ligament, where it can pull off of the bone

- Grade 1 sprain (mild). The ligament is stretched, but not torn.

- Grade 2 sprain (moderate). The ligament is partially torn. This type of injury may involve some loss of function.

- Grade 3 sprain (severe). The ligament is completely torn or is pulled off its attachment to the bone. These are significant injuries that require medical or surgical care. If the ligament tears away from the bone, it may take a small chip of the bone with it. This is called an avulsion fracture.

Cause

Symptoms

- Depending on the severity of the sprain, you may or may not experience pain at the time of the injury.

- You may have bruising, tenderness, and swelling around the affected finger joint.

- If a ligament is completely torn, the finger joint may feel loose or unstable.

- Proper and prompt diagnosis and treatment of a finger injury is necessary to avoid long-term complications, including chronic pain, instability, and arthritis.

- In addition, some finger sprains are not sprains at all; they are misdiagnosed fractures or dislocations of the finger, which need to be addressed promptly to avoid permanent dysfunction.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Imaging Tests

Other imaging tests. If more information is needed, your doctor may order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan or an ultrasound. These tests can help your doctor learn more about the severity of your injury and make decisions about your treatment and return to activity.

Treatment

Treatment for a sprained finger depends on the severity of the injury.

Home Care

- Rest. Try not to use your hand strenuously for at least 48 hours.

- Ice. Apply ice immediately after the injury to keep the swelling down. Use cold packs for 20 minutes at a time, several times a day. Do not apply ice directly to the skin.

- Compression. Wear an elastic compression bandage to reduce swelling. Do not make the bandage too tight, as this could cut off blood flow to the finger.

- Elevation. As often as possible, rest with your hand raised up higher than your heart.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

- Reconnecting the ligament to the bone and/or

- Repairing the avulsion fracture (ligament with a pulled-off piece of bone attached to it) using a pin, screw, or special bone anchor.

After surgery, you may have to wear a short arm cast or a splint for a few weeks to protect the ligament while it heals. You will then likely start therapy to get the finger moving and avoid stiffness.

Outcomes

When diagnosed and treated properly, most finger sprains will heal well with few complications. However, ignoring a sprained finger with the hope that it will heal on its own may lead to long-term problems, including chronic instability, weakness, stiffness, and arthritis.

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.