Diseases & Conditions

Joint Replacement Infection

Total knee and total hip replacements are two of the most commonly performed elective operations. For the majority of patients, joint replacement surgery relieves pain and helps them to live fuller, more active lives.

No surgical procedure is without risks, however. A small number of patients undergoing hip or knee replacement (about 1 in 100, or 1%) may develop an infection after the operation.

- Joint replacement infections may occur in the wound or deep around the artificial (metal and plastic) implants.

- An infection may develop during your hospital stay or after you go home.

- Joint replacement infections can even occur years after your surgery.

This article discusses:

- Why joint replacements may become infected

- The signs and symptoms of infection

- Treatment for infections

- Ways to help prevent infections

Description

Any infection in your body can spread to your joint replacement.

Infections are caused by bacteria. Although bacteria are abundant in our gastrointestinal (GI) tract and on our skin, they are usually kept in check by our immune system. For example, if bacteria make it into our bloodstream, our immune system rapidly responds and kills the invading bacteria.

However, because joint replacements are made of metal and plastic, it is difficult for the immune system to attack bacteria that make it to these implants. Bacteria like to stick to metal. Since the metal implant does not receive any blood flow, our immune system has a hard time identifying the bacteria, so it does not know how to respond and kill it. If bacteria gain access to the implants, they may multiply and result in a joint infection.

Despite antibiotics and preventive treatments, patients with infected joint replacements often require surgery to cure the infection.

Cause

A total joint may become infected during the time of surgery, or anywhere from weeks to years after the surgery.

The most common ways bacteria enter the body include:

- Through breaks or cuts in the skin

- During major dental procedures (such as a tooth extraction or root canal)

- Through wounds from other surgical procedures

Some people are at a higher risk for developing infections after a joint replacement procedure. Factors that increase the risk of infection include:

- Immune deficiencies (such as HIV or lymphoma)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Peripheral vascular disease (poor circulation to the hands and feet)

- Immunosuppressive treatments (such as chemotherapy or corticosteroids)

- Obesity

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of an infected joint replacement include:

- Increased pain or stiffness in a previously well-functioning joint

- Swelling

- Warmth and redness around the wound

- Wound drainage (blood, pus, or other fluids that come out of the wound)

- Fevers, chills, and night sweats

- Fatigue

Doctor Examination

When total joint infection is suspected, early diagnosis and proper treatment increase the chances that you can keep the implants. Your doctor will discuss your medical history and conduct a detailed physical examination.

Tests

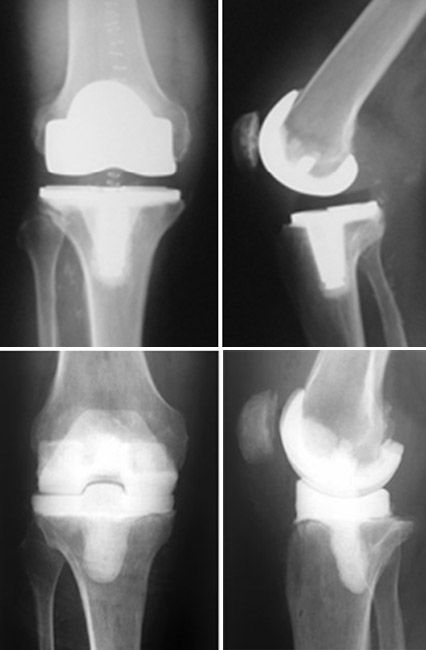

Imaging tests. X-rays and bone scans can help your doctor determine whether there is an infection in the implants.

Laboratory tests. Specific blood tests can help identify an infection. For example, in addition to routine blood tests like a complete blood count (CBC), your surgeon will likely order two blood tests that measure inflammation in your body:

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

Although neither test will confirm the presence of infection, if the CRP and/or ESR are elevated, it raises the suspicion that an infection may be present. If the results of these tests are normal, it is unlikely that your joint is infected.

Additionally, your doctor will analyze fluid from your joint to help identify an infection. To do this, they use a needle to draw fluid from your hip or knee. The fluid is examined under a microscope for the presence of bacteria and is sent to a laboratory. There, it is monitored to see if bacteria or fungus grows from the fluid.

The fluid is also analyzed for the presence of white blood cells. In normal hip or knee fluid, there is a low number of white blood cells. The presence of a large number of white blood cells (particularly cells called neutrophils) indicates that the joint may be infected. The fluid may also be tested for specific proteins that are known to be present when there is an infection.

Other technologies, such as Synovasure, may also be used to test the synovial fluid. Synovasure is a test that looks for a specific protein within the synovial fluid to help detect the presence of an infection.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

In some cases, only the skin and soft tissues around the joint are infected, and the infection has not spread deep into the artificial joint itself. This is called a "superficial infection." If the infection is caught early, your doctor may prescribe intravenous (IV) or oral antibiotics.

This treatment has a good success rate for early superficial infections.

Surgical Treatment

Infections that go beyond the superficial tissues and gain deep access to the artificial joint almost always require surgical treatment.

Debridement. Deep infections that are caught early (within several days of their onset), and those that occur within weeks of the original surgery, may sometimes be cured with a surgical washout of the joint.

- During this procedure, called debridement, the surgeon removes all contaminated soft tissues.

- The implant is thoroughly cleaned, and plastic liners or spacers are replaced.

- After the procedure, intravenous (IV) antibiotics are prescribed for approximately 6 weeks.

Staged surgery. In general, the longer the infection has been present, the harder it is to cure without removing the implant.

Late infections (those that occur months to years after the joint replacement surgery) and infections that have been present for longer periods of time almost always require a staged surgery.

The first stage of this treatment includes:

- Removal of the implant

- Washout of the joint and soft tissues

- Placement of an antibiotic spacer

- Intravenous (IV) antibiotics

An antibiotic spacer is a device placed into the joint to maintain normal joint space and alignment. It also improves the patient's comfort and mobility while the infection is being treated.

Spacers are made with bone cement that is loaded with antibiotics. The antibiotics flow into the joint and surrounding tissues and, over time, help to eliminate the infection.

Patients who undergo staged surgery typically need at least 6 weeks of IV antibiotics, or possibly more, before a new artificial joint can be implanted.

Orthopaedic surgeons work closely with other doctors who specialize in infectious diseases. These infectious disease doctors help determine:

- Which antibiotic(s) you will be on

- Whether the antibiotics will be intravenous (delivered through a tube inserted into the arm) or oral (taken by mouth)

- The duration of therapy

They will also obtain periodic blood work to evaluate the effectiveness of the antibiotic treatment.

Once your orthopaedic surgeon and the infectious disease doctor determine that the infection has been cured (this usually takes at least 6 weeks), you will be a candidate for a new total hip or knee implant (called a revision surgery). This second procedure is stage 2 of treatment for joint replacement infection.

During revision surgery, your surgeon will:

- Remove the antibiotic spacer

- Repeat the washout of the joint

- Implant new total knee or hip components

Single-stage surgery. In this procedure, the implants are removed, the joint is washed out (debrided), and new implants are placed all in one stage.

Single-stage surgery is not as popular as two-stage surgery, but it is gaining wider acceptance as a method for treating infected total joints. Doctors continue to study the outcomes of single-stage surgery.

Prevention

At the time of original joint replacement surgery, there are several measures taken by your healthcare team to minimize the risk of infection. Some of the steps have been proven to lower the risk of infection, and some are thought to help but have not been scientifically proven. The most important known measures to lower the risk of infection after total joint replacement include:

- Antibiotics before and after surgery. Antibiotics are given within 1 hour of the start of surgery (usually once in the operating room) and continued at intervals for 24 hours following the procedure.

- Short operating time and minimal operating room traffic. Efficiency in the operation by your surgeon helps to lower the risk of infection by limiting the time the joint is exposed. Limiting the number of operating room personnel entering and leaving the room is also thought to decrease the risk of infection.

- Use of strict sterile techniques and sterilization of instruments. Care is taken to ensure the operating site is sterile, the instruments have been autoclaved (sterilized) and not exposed to any contamination, and the implants are packaged to ensure their sterility.

- Preoperative nasal screening for bacterial colonization. There is some evidence that testing for the presence of bacteria (particularly the Staphylococcus species) in the nasal passages several weeks before surgery may help prevent joint infection. In institutions where this is performed, patients who are found to have Staphylococcus in their nasal passages are given an intranasal antibacterial ointment before surgery. The type of bacteria that is found in the nasal passages may help your doctors determine which antibiotic you are given at the time of your surgery.

There are also things you should (and should not) do at home before your procedure to reduce your risk of infection:

- Preoperative chlorhexidine wash. There is evidence that home washing with a chlorhexidine solution (often in the form of soaked cloths) in the days leading up to surgery may help prevent infection. This may be particularly important if patients are known to have certain types of antibiotic-resistant bacteria on their skin or in their nasal passages (see above). Your surgeon will talk with you about this option.

- Skin assessment.

- In the weeks leading up to your surgery, tell your doctor about any skin irritations on the limb that is being operated on, including cuts, scratches, abrasions (scrapes), rashes, or bug bites. Any break in the skin gives bacteria a chance to enter your body and cause an infection, and if you have an infection, your procedure will be cancelled.

- The day of your surgery, do a good skin assessment in the mirror. Look all over your skin, including in the groin area, under the breasts, behind the knees, and under the arms. Report anything abnormal to your doctor.

- Do not shave the area of the surgery. If shaving is necessary, it will be done in the hospital.

Long-term Infection Prevention

If you have had a joint replacement, your surgeon may prescribe antibiotics before you have dental work. This is done to protect the implants from bacteria that might enter the bloodstream during the dental procedure and cause infection.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has developed recommendations for when antibiotics should be given before dental work and which patients would benefit. In general, most people do not require antibiotics before dental procedures. There is little evidence that taking antibiotics before dental procedures is effective at preventing infection.

See the suggested timing for having dental procedures before and after total hip or knee replacement surgery.

To assist doctors in the diagnosis and prevention of surgical site infections and periprosthetic joint infections, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has conducted research to provide some useful guidelines. These are recommendations only and may not apply to every case. For more information: Plain Language Summary - Clinical Practice Guideline - Surgical Site Infections - AAOS and Plain Language Summary - Clinical Practice Guideline - Periprosthetic Joint Infections - AAOS

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.