Diseases & Conditions

Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma is a malignant (cancerous) tumor that usually begins growing in a bone. It occurs primarily in children and young adults, often appearing between the ages of 10 and 20 years.

Most commonly, Ewing sarcoma develops in the long bones of the leg or arm or in flat bones like the pelvic bone, scapula (shoulder blade), or ribs. Usually, Ewing sarcoma originates in a bone, but occasionally, the tumor begins in the muscles, soft tissues, or other organs (this is called extraosseous Ewing sarcoma).

Ewing sarcoma is very rare, accounting for less than 1% of all pediatric cancers. There are only about 200 to 300 new cases each year in the U.S. However, although it is rare compared to other types of cancer, Ewing sarcoma is the second most common bone cancer in children and young adults. According to data on children younger than 15 years old, approximately 1.7 children out of 1 million develop the disease.

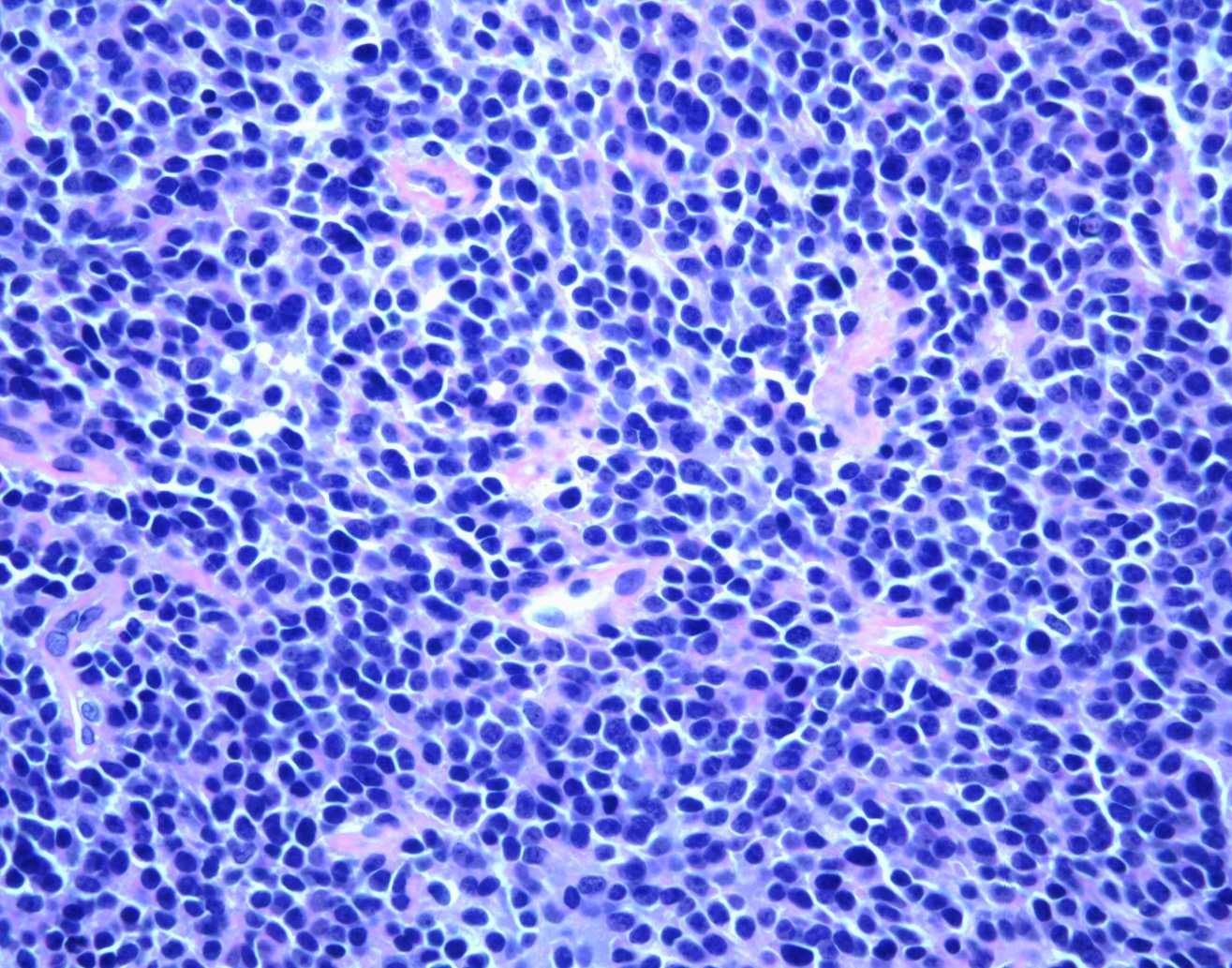

Ewing sarcoma is in the family of small blue cell (round cell) tumors due to its appearance under a microscope. Recently, doctors have defined the disease to include four types of cancer, referred to as the Ewing family of tumors (EFTs):

- Ewing sarcoma of bone

- Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma

- Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), which may occur in both bone and soft tissue

- Askin's tumor, a PNET that occurs in the bones of the chest

This article focuses on Ewing sarcoma of bone.

Cause

There is no known cause of Ewing sarcoma.

Most cancers are known to develop from a certain kind of tissue or organ. For example, breast cancer develops from breast cells. In the case of Ewing sarcoma, however, doctors do not know the exact type of cell where the cancer starts.

What we do know is that the cancer forms when changes occur in a cell's chromosomes, or DNA. In Ewing sarcoma cells, the genetic material in chromosomes #11 and #22 is mismatched. This genetic abnormality is not inherited from a child's parents — the chromosomal changes occur after a child is born.

It is not understood why this abnormality occurs. Doctors have not identified any risk factors that make one person more at risk than another. The tumor does not develop as a result of any dietary, social, or behavioral habits. There are no known ways to prevent the disease, and patients or their parents should know that there is nothing they could have done differently to prevent these tumors.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of Ewing sarcoma include:

- Bone pain not caused by an injury that does not go away

- A growing lump or bump that may feel soft or warm

- Pain, swelling, and/or tenderness at the site of the tumor

However, the tumor may be present for many months before it becomes large enough to cause pain and swelling. In some cases, the first symptom of Ewing sarcoma is the presence of a mass.

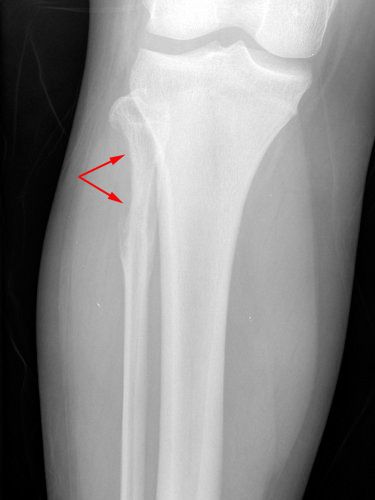

Although injuries are not a known cause, an injury may draw attention to a tumor. For example, a bone weakened by a tumor may break after a minor injury. This is called a pathologic fracture.

Sometimes, Ewing sarcoma can affect the entire body, and patients may experience symptoms like fever, body aches, weight loss, or fatigue (tiredness).

Doctor Examination

After discussing symptoms and conducting a physical examination, the doctor will use several types of tests to diagnose Ewing sarcoma.

Imaging Tests

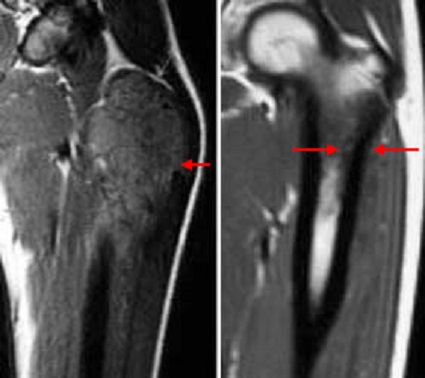

First, the doctor uses imaging tests to create detailed pictures of the affected area. These may include X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, computerized tomography (CT) scans, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

Biopsy

To diagnose the tumor, the doctor will do a biopsy. This procedure involves taking a piece of tissue from the tumor and looking at it under a microscope. A biopsy may be done in either an operating room or X-ray department.

Ewing sarcoma tumors are sometimes called small blue cell (round cell) tumors because of the way they look under a microscope.

Staging

Once the tumor is identified as Ewing sarcoma, the doctor will conduct more tests to determine whether the cancer has spread. This process is known as staging. These additional tests may include:

- Blood tests

- CT scan of the lungs

- PET scan

- Bone marrow biopsy

The part of the body where the first tumor develops is called the primary site. Any parts of the body where it has spread are called metastatic sites. Ewing sarcoma most commonly metastasizes to the lungs, but it can spread to other bones, bone marrow, and other sites in the body.

By identifying the stage of the tumor, the doctor can determine the most effective treatment strategy for you or your child.

Treatment

The most common treatment regimen for Ewing sarcoma involves:

- Chemotherapy. At the time of diagnosis, many cases of Ewing sarcoma have not spread to other parts of the body. Even if tests do not show spread, however, doctors will plan a treatment strategy that assumes a very small amount of spread (micrometastatic disease) has already happened. Accordingly, chemotherapy is usually the first, most important line of treatment.

- Local control (with surgery, radiation, or a combination of both). After several cycles of chemotherapy, the next step is local control. This means surgically removing or killing the primary tumor cells. In most cases, if possible, doctors use surgery to remove the tumors. Radiation treatment is used only when surgery cannot completely remove the tumor or would cause the patient to lose function in the affected area. Typically, physicians work in teams to tailor their recommendation of surgery and/or radiation to each patient's specific situation.

- More chemotherapy. After recovery from surgery and/or radiation, chemotherapy will be resumed to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells. It generally takes close to 1 year to finish all the cycles of chemotherapy.

Many types of physicians work together to treat Ewing sarcoma. These include orthopaedic surgical oncologists, pediatric or adult medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists. Because Ewing sarcoma treatment requires coordination of care between all of these specialists, most Ewing sarcoma patients are treated at major hospital institutions or cancer centers.

Chemotherapy

Pediatric and adult medical oncologists specialize in giving chemotherapy or other medications (e.g., immunotherapy, targeted therapy) to treat cancer.

Chemotherapy is a drug treatment used to kill the primary tumor and any spread of the cancer. It is often used initially to shrink the primary tumor and make it easier to remove with surgery.

Because chemotherapy treatment for Ewing sarcoma lasts for a length of time, the drugs are given through a special IV called an indwelling central venous catheter. This is a very thin tube that is inserted into a vein in the chest and stays in place until the end of treatment. It is placed just before chemotherapy treatment is started.

Chemotherapy is done in cycles. It uses combinations of various drugs to destroy cancer cells. Because these drugs affect the entire body system, healthy cells can also be damaged, including white blood cells and platelets. The rest period between cycles allows the blood cell count to recover, but there are still side effects from the cell damage. The most common side effects include hair loss, nausea, mouth sores, and fevers. Certain medicines can help relieve some side effects.

Various medications are used in chemotherapy treatment for Ewing sarcoma. The most common drugs go by the abbreviation VAC/IE (or VDC/IE):

- Vincristine

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- Cyclophosphamide

- Ifosfamide

- Etoposide

Many advances in chemotherapy have been made through knowledge gained by placing patients in clinical trials. Physicians request permission to enroll patients in specific clinical trials. Your or your child's doctor can tell you more about any clinical trials currently being held.

Surgery

The main goal of tumor surgery is to remove the tumor entirely and keep it from returning. The secondary goal is to reconstruct the limb to offer the patient the best possible function. Most of the time, limb salvage is possible, though occasionally, an amputation is the best option.

Sarcoma surgery requires surgeons to remove all of the bone affected by the tumor and a margin of healthy tissue around the tumor. Then, orthopaedic surgeons can reconstruct the bone, joint, or soft tissue site.

Most commonly, there are several options for reconstruction that may use bone grafts, artificial joints, or a combination of both. The goal is to restore the body part so the patient can do their normal, everyday activities.

You can think of reconstruction options using the following categories:

- Arthroplasty (large joint replacements with metal parts replacing damaged natural parts)

- Allograft (cadaver bone used to rebuild the bone that was removed)

- Autograft (the patient's own bone, such as a fibula to reconstruct the bone removed)

- Allograft prosthetic composite (APC) — a combination of cadaver bone and joint replacement

- Amputation (including rotationplasty)

The amount of function that can be restored from reconstructive surgery depends on how much muscle and joint tissue can be preserved (saved) while still removing the entire tumor. The most important goal is always to help the patient become cancer-free and lower the chance that the tumor will come back.

Depending on the site of surgery, the patient may need to limit putting weight on the reconstructed limb. Ongoing rehabilitation with physical therapy is necessary to return to daily activities. A physical therapist may provide exercises to help maintain range of motion and restore strength.

Strenuous or athletic activities are likely to cause too much stress or wear on the reconstruction, but occasionally some patients will still attempt to perform these activities. Most patients, however, will not be able to do such activities due to the amount of muscle and joint tissue removed.

Some patients may need more operations to keep the limb functioning for the rest of their lives. Reconstruction of a bone in a growing child is a special challenge. In some cases, doctors have the technology to build custom metal joint replacements that can be lengthened over time with a magnet or small surgeries to expand the implant. As the child grows, multiple procedures may be needed to lengthen the reconstructed bone.

It is important to consider the risks and complications associated with the surgery. Infections, problems with the artificial joint, and wound healing are the most frequent concerns.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy can destroy cancer cells and shrink tumors. It is most often used to lower the chance of the primary tumor recurring (coming back). Radiation may also be used instead of surgery at sites where surgery is too risky or complicated. Occasionally, radiation therapy is used in conjunction (along) with surgery.

When radiation treatment is used, daily treatments are given over the course of many weeks. While the discomfort of surgery may be avoided, there are risks associated with the radiation, including:

- Skin damage

- Muscle scarring and loss of joint flexibility

- Damage to nearby organs

- Loss of bone growth in growing children

- Secondary cancers caused by radiation

- Chronic swelling of an arm or leg

- Slow wound healing

Outcomes

Over the years, the outcome of treatment for patients with Ewing sarcoma has improved a great deal. This is thanks to advances in chemotherapy, diagnostic imaging, and reconstructive techniques.

Prognosis varies from patient to patient but, in general, 77% of patients without any spread of the disease will survive at least 5 years after diagnosis with standard treatment.

Several factors can improve the likelihood of survival. These include:

- No known spread of the cancer

- An excellent response to chemotherapy

- Primary tumors being located in the arms and legs, instead of the pelvis

- Complete removal of the tumor

Survivors of Ewing sarcoma require continued follow-up care to monitor any late side effects from treatment, and any recurrence of the tumor. When tumors come back, it usually happens within the first few years after treatment.

Research on the Horizon

Treatment for Ewing sarcoma will change in the years to come as new knowledge becomes available. Current research on the Ewing family of tumors has focused on many areas.

The meaning of the chromosomal abnormality is not known, nor is it known how this affects normal cellular function. Increased knowledge in this area could someday lead to newer therapies that can target the abnormalities in cellular function.

Other investigations involve chemotherapy and address issues about proper drug dosage and the best combinations of drugs. Doctors are also looking at various types of bone marrow transplants.

Biomechanical engineers and surgeons are always making improvements to artificial joints. Expandable prostheses, which can be lengthened as a child grows, are helping many children who would once have required an amputation to keep their limbs.

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.