Diseases & Conditions

Chronic Shoulder Instability

This article was written and/or reviewed by a member of American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES).

The shoulder joint has the greatest range of motion of any joint in your body. It can reach up over your head and behind your back, and it can rotate in many directions. While this is helpful to put your hand in almost any position and to interact with the world around you, it can also cause instability.

Shoulder instability occurs when the humerus (head of the upper arm bone) is forced out of the glenoid (shoulder socket), or dislocates. This typically happens at first as the result of a sudden injury, such as a fall or accident.

Once a shoulder has dislocated, it is vulnerable to dislocating again. When the shoulder is loose and slips out of place repeatedly, it is called chronic shoulder instability.

Anatomy

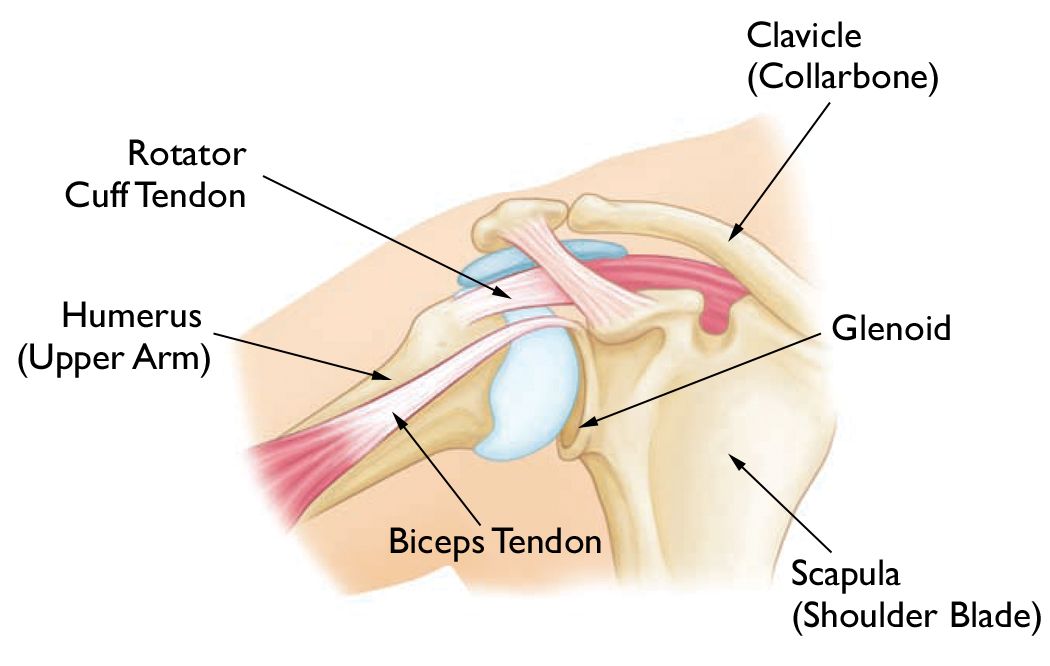

The shoulder is made up of three bones:

- The humerus (upper arm bone)

- The scapula (shoulder blade)

- The clavicle (collarbone)

The head, or ball, of the upper arm bone fits into a shallow socket in the shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. Strong connective tissue, called the shoulder capsule, is the ligament system of the shoulder and keeps the head of the upper arm bone centered in the glenoid socket. This tissue covers the shoulder joint and attaches the upper end of the arm bone to the shoulder blade.

The shoulder also relies on strong tendons and muscles to keep it stable.

Description

- When the ball of the upper arm comes partially out of the socket, this is called a subluxation.

- A complete dislocation means the ball comes all the way out of the socket.

- Once the ligaments, tendons, and muscles around the shoulder become loose or torn, dislocations can occur repeatedly. Chronic shoulder instability is the persistent inability of these tissues to keep the arm centered in the shoulder socket.

Cause

Shoulder Dislocation

Severe injury, or trauma, is often the cause of an initial shoulder dislocation.

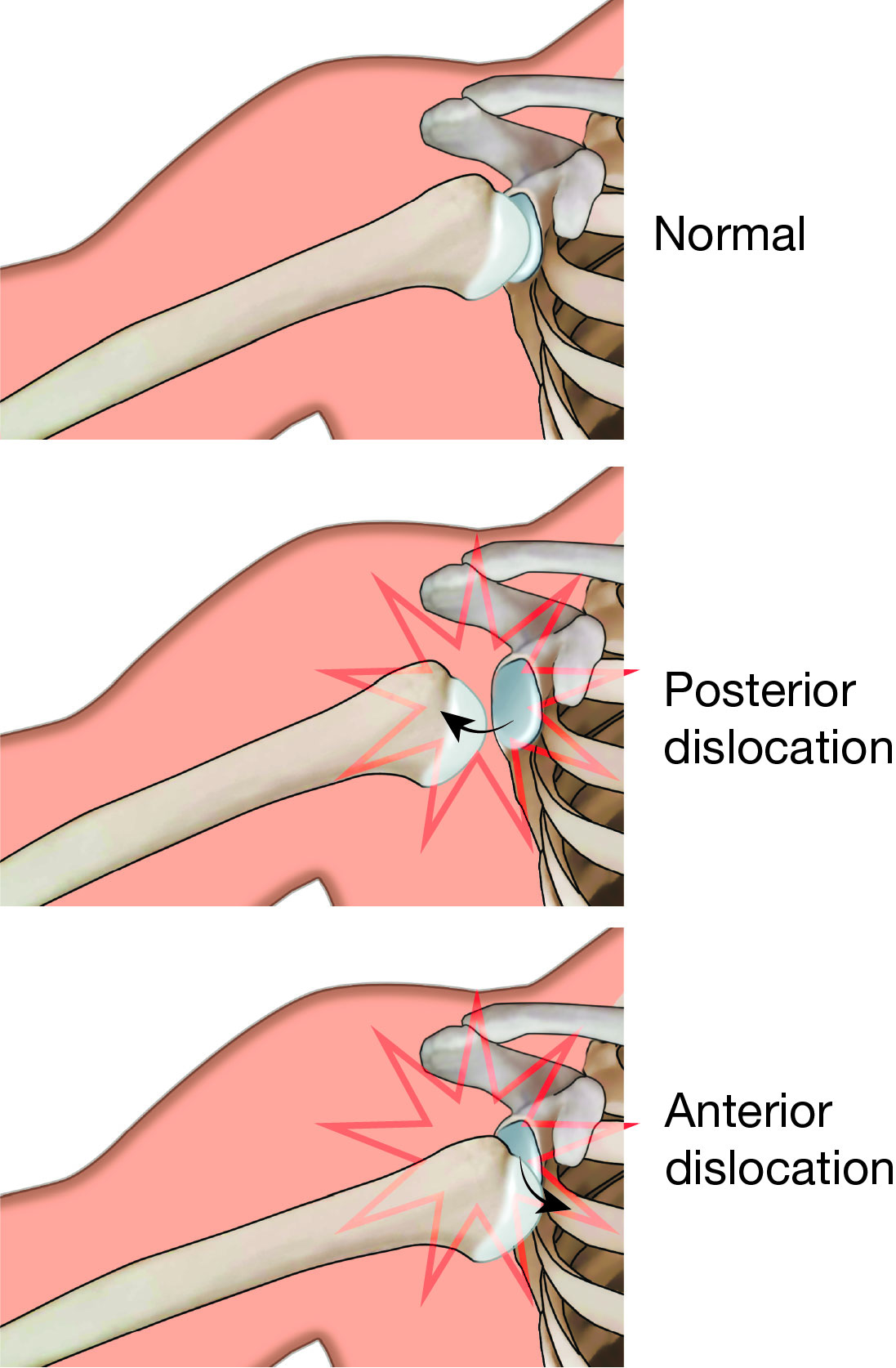

- When the head of the humerus dislocates, the socket (glenoid) and the ligaments in the front of the shoulder are often injured. This is called an anterior dislocation.

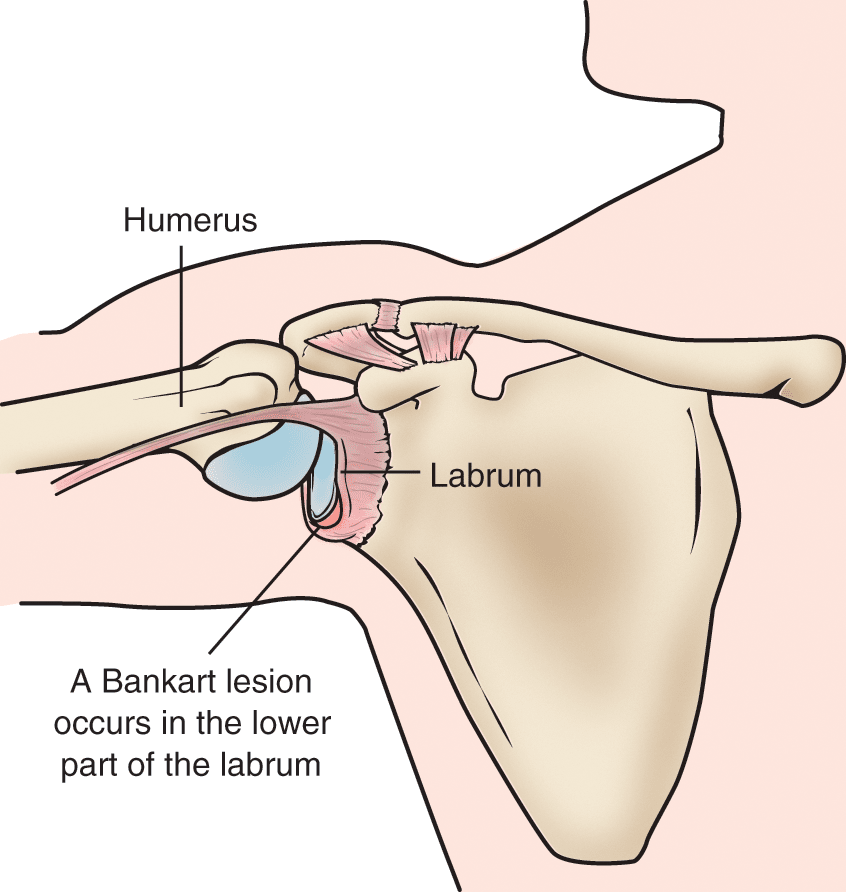

- The labrum — the cartilage rim around the edge of the glenoid — may also tear. This is commonly called a Bankart lesion.

- While the shoulder most commonly dislocates toward the front, it can also dislocate backward, leading to a posterior dislocation and what is known as a reverse Bankart lesion.

A first dislocation can lead to continued dislocations, giving out, or a feeling of instability in the shoulder.

Hyperlaxity

Some people with shoulder instability have never had a dislocation. Most of these patients have looser ligaments in their shoulders. When this increased looseness is just your normal anatomy, it is called hyperlaxity.

Sometimes, the looseness is the result of repetitive overhead motion. Swimming, tennis, and volleyball are among the sports requiring repetitive overhead motion that can stretch out the shoulder ligaments. Many jobs also require repetitive overhead work.

Looser ligaments can make it hard to maintain shoulder stability. Repetitive or stressful activities can challenge a weakened shoulder. This can result in a painful, unstable shoulder.

In a small minority of patients, the shoulder can become unstable without a history of injury or repetitive strain. In such patients, the shoulder may feel loose or dislocate in multiple directions, meaning the ball may dislocate out the front, out the back, or out the bottom of the shoulder. This is called multidirectional instability. These patients have naturally loose ligaments throughout the body and may be double-jointed.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of chronic shoulder instability include:

- Repeated shoulder dislocations

- Repeated instances of the shoulder giving out

- A persistent sensation of the shoulder feeling loose, slipping in and out of the joint, or just hanging there

- Pain caused by shoulder injury

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination and Patient History

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. Specific tests help your doctor assess instability in your shoulder. Your doctor may also test for general looseness in your ligaments. For example, you may be asked to try to touch your thumb to the underside of your forearm.

Imaging Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to help confirm your diagnosis and identify any other problems.

X-rays. X-rays will show any injuries to the bones that make up your shoulder joint.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. An MRI provides detailed images of soft tissues. It may help your doctor identify injuries to the ligaments and tendons surrounding your shoulder joint.

In some cases, the doctor may order an arthrogram, in which dye is injected into the shoulder joint, and an MRI scan is then taken. This test may show more subtle (less obvious) injuries.

Computed tomography (CT) scan. Sometimes, the doctor may order a CT scan to assess the bones that make up the shoulder joint. With repeated dislocations or subluxations, some bone loss may occur on either the socket or humerus.

Treatment

Chronic shoulder instability is often first treated with nonsurgical options. If these options do not relieve the pain and instability, you may need surgery.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Your doctor will develop a treatment plan to relieve your symptoms. It often takes several months of nonsurgical treatment before you can tell how well it is working. Nonsurgical treatment typically includes:

Activity modification. You must make some changes in your lifestyle and avoid activities that aggravate your symptoms.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen can reduce pain and swelling.

Physical therapy. Strengthening shoulder muscles and working on shoulder control can increase stability. Your physical therapist will often design an additional home exercise program for your shoulder.

Surgical Treatment

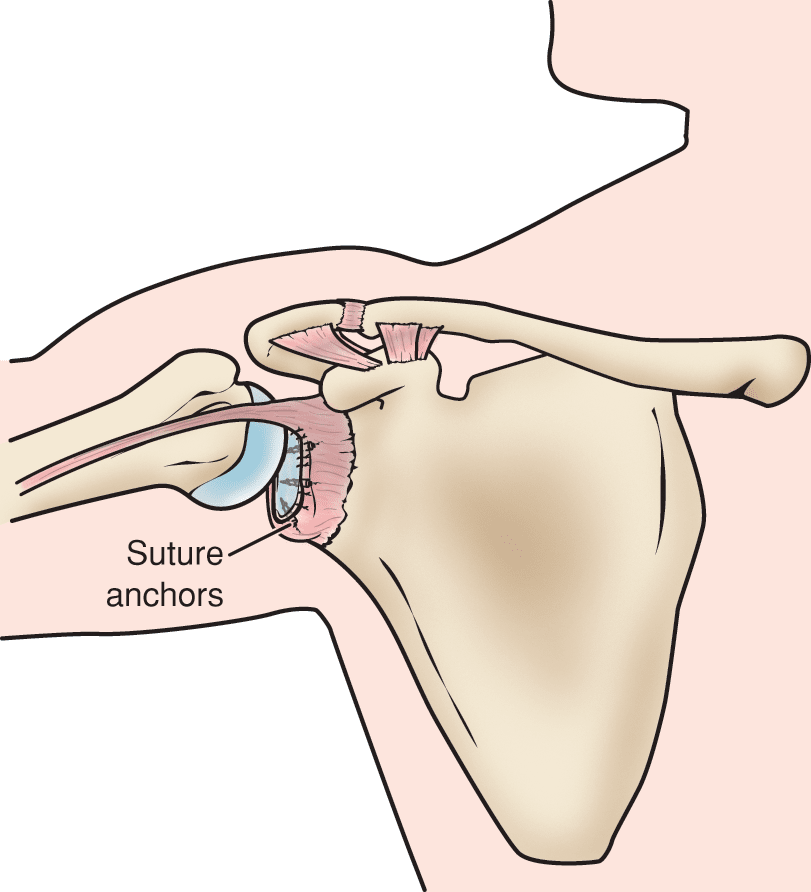

Surgery is offered to patients with repeated dislocations to repair torn or stretched ligaments so the ligaments are better able to hold the shoulder joint in place.

Other issues caused by the instability — such as bone loss on the socket or humerus — may also need to be addressed with surgery. Your doctor will discuss this with you after reviewing your imaging.

Arthroscopy. Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure used to repair soft tissues in the shoulder. Your surgeon will look inside the shoulder with a tiny camera and perform the surgery with special pencil-thin instruments. Arthroscopy is a same-day or outpatient procedure.

Open Surgery. Some patients may need an open surgical procedure. This involves making an incision over the shoulder and performing the repair under direct visualization.

Rehabilitation. After surgery, your shoulder may be immobilized temporarily with a sling.

When the sling is removed, you will begin exercises to rehabilitate the ligaments and muscles. These exercises will improve the range of motion in your shoulder and prevent scarring as the ligaments heal. Your physical therapist will gradually expand your rehabilitation plan by adding exercises to strengthen your shoulder.

Be sure to follow the treatment plan your doctor gives you. Although it is a slow process, your commitment to physical therapy is the most important factor in returning to all the activities you enjoy.

Contributed and/or Updated by

Peer-Reviewed by

AAOS does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products, or physicians referenced herein. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific orthopaedic advice or assistance should consult his or her orthopaedic surgeon, or locate one in your area through the AAOS Find an Orthopaedist program on this website.